Christal

Cooper

*Article

With Excerpts – 2,902 Words

All

excerpts have been given copyright privilege by Re’Lynn Hansen and White Pine

Press

Re’Lynn

Hansen’s

To Some Women I Have Known:

To Some Women I Have Known:

Exploring Memory,

Memoir, Meaning

& Death in Poetry

To Some Women I Have Known, published by White

Pine Press in April of 2015, is Re’Lynn Hansen’s first full- length poetry

collection.

Hansen, who is Associate Professor in the

Creative Writing Department of Columbia College in Chicago, breaks the rules

and so eloquently by crossing the boundaries of form in poetry: it is not limited to traditional form, but in

memoir, essay, narrative, research and news reporting.

To Some Women I Have Known takes the reader on an

emotional, spiritual, and mental journey, leaving the reader at a loss for

breath, the reader’s heart beating so wildly it feels like the reader has two hearts

instead of one.

This collection explores the questions that

every individual faces: What is

meaning? What is happiness? What is death? And what role does memoir, memory, and

meaning play in our quest to find the answer to the first two questions and

conquer the latter?

In her quest for these answers Hansen finds

comfort in the women in her life. These

women are the main focus in To Some Women I Have Known.

The first poem from this collection Hansen wrote

is “From Where I Stand on the Steps of the Romanesque Church” where she

attended her brother’s wedding and experienced a hyperawareness – living in a

specific moment and how that same specific moment is already dying.

“This happened at my brother’s wedding, on a

beautiful day, as I was standing on the steps of the church watching everyone

arrive in their tuxes and formals. And

even as I was living it, or trying to live it, I was already remembering how

singular and beautiful and great it was, and how I would remember it. I stood there aware that my grandmother, who

was arriving, was dying of cancer, and I went into

the act of remembering that moment already” (from an interview with Re’Lynn

Hansen, Sept 2015).

From Where I Stand

on the Steps of the Romanesque Church

Weddings seem unreal to me, and so it seems

that I am not here, but only that I remember I was here. I’m already remembering how I stand on the

steps of the Romanesque church and look at the vines growing gracefully on the

building across the street and how the Cadillacs turn into the parking lot –

which seems an old thing – to have Cadillacs arcing along the shaded vine-wall

of the church parking lot. What era was

that? And I am already remembering how I

will remember it. Providing it might be

something worth remembering. That it

might be something. Tony Lamont, an old

friend of Aunt Ag’s, is getting the wheelchair from the trunk of the Cadillac. He wears the painted-pony cowboy boots for

Aunt Aug, who still flirts with the man she went skiing with in Aspen thirty

years ago. My younger cousins, two girls

sixteen and eighteen, who will never be sixteen and eighteen, again, each go to

help my grandmother and slowly settle her into the chair. The linen dress of my grandmother is now

pressed into the chair and pulled out at the sides, like the wings of a moth

caught in the daytime screen. My cousins

close in around the woman in the wheelchair, each touching her shoulder

lightly. My aunt has her own moment to

shimmer as the sun dapples the street and plays upon the ice-blue gown pooled

briefly at her feet like water. The

girls wear ruffled dresses that swish as they walk. They look both ways before crossing the

street under the elms. I am already

remembering the orange and yellow dresses flashing light in the open

canopy. Aunt Ag, and Tony, the two

girls, and the grandmother in the wheelchair come toward me where I stand on

the steps of the Romanesque church.

This

hyperawareness is felt in all of the poems where, even as a 12-year old girl,

Hansen understands the preciousness of the moment.

In “One Night a Girl Appeared to Me” 12-year

old Hansen has just moved from Oak Park, a suburb of Chicago, to the city,

where she lives in a Victorian neighborhood and finds herself fascinated by the

neighborhood girl and the helicopter pad at the end of her block.

“As a twelve year old, I thought I found ‘truth’

just sitting in my bedroom, writing poems.

My parents were creative people.

My father liked to draw; my mother painted. Their actual professions were as investors in

real estate. Even in that arena they

were creative thinkers. I didn’t grow up

around books, but they bought me the books that I wanted. My parents are great entertainers and socializers,

and at every party they’d have me read a poem.

They’d hush and shush everyone and actually get them to listen. I’d have this frozen audience standing there

with their martini glasses and double malts.

But I think they did listen, and I developed this broad idea of audience

as a consequence” (from an interview with Re’Lynn Hansen, 2015).

It is the first poem, “The Ghost Horse,” that the reader is introduced to Re’Lynn, who is

the audience, and June, who is the active participant. Both women are on their quest to find out

what the meaning of life is.

We were going to get a horse. The horse would give us meaning or a feeling

we didn’t have sitting in lecture halls during the day or waiting the tables at

night.

We would ride the horse from Illinois to

Colorado and meet people along the way who would also give us meaning.

It is June that has the courage to climb

on the horse, and Hansen who has the courage to observe this pivotal

moment.

Then for a moment June looked like a god on a

horse, straight in the saddle. It was as

we had imagined ourselves – we who did not believe in god, but horses.

In “Patty Hearst on the Prairie” Hansen is a 19

year old girl who has yet to apply for college, and is instead focused on death

– her friend Nikki’s mother is on her deathbed:

There was only the caretaker

ushering us to the corners of the bed.

There were chairs, but we stood.

Nikki was out.

Nikki is out? We

repeated to the caretaker.

There was that high school spike in our

voice. Didn’t she

know we had come to say goodbye to her mother?

We had come to affirm something.

All the curtains were pulled back from the

floor-to-ceiling windows,

A shimmering display around the bed.

I thought:

She was a daughter herself of someone.

Excerpt from “Patty Hearst on the Prairie”

The 19 year old Hansen is losing her

youth, her pure ideals, and is facing death.

To the young Hansen, one year after graduating

from high school, finding Patty Hearst would be an escape from the reality of

her day:

I had a book by Unamuno

but was looking for Patty Hearst

among the airport crowd

as I stared at the open skies and ledger

boards

listing destinations.

I listened to airport announcements

At any moment she would come, fronting the crowds

a ghost ship emerging

armed with submachine guns.

I closed my eyes

to see the essence

escaping me.

It took a variety of majors (accounting,

psychology, Spanish, English Literature, and Journalism) before Hansen finally settled

on a degree in Creative Writing. It was

during her days as a graduate student in Creative Writing at Columbia College

Chicago that she finally came to the realization that she was a writer.

“Everyone in my program

thought we were experiencing the intensity and inventing the DNA of a writing

program for the first time. We’d have

great, 2:00 a.m. arguments about Faulkner, Pound, Wright. I was passionate about Marguerite Duras’ “The

Lover” as I was about any real lover.

We’d hang out at our floppy grad school apartments and have impromptu

readings – then depart for a neighborhood dive bar” (from an interview with

Hansen 2015).

The question of death, and how to conquer

it in addition to what is meaning and happiness is answered in the last stanza

of the poem “25 Sightings of the Ivory Billed Woodpecker,” where Hansen surmises

that it is in our questioning that something we desire comes into being:

A

documentarian, making a movie about the bird, mentioned that there is less to

say about extinct woodpeckers than about your yearning to look for and even see

them, whether they are there or not.

In the prose poem “Woman in a Coma Had Taken

Drug” Hansen and June are at a beach hotel in Guatemala when they read about

Karen Ann Quinlan, whom Hansen identifies with:

The lobby tables of the American hotels were

always strewn with American papers, tossed there by tourists who had had their

morning coffee and who were now out in hired taxis touring the

countryside. Nixon had resigned. The

Vietnam War had ended. The newspapers

were back to following people. All of

the stories outlined the life of Karen Ann Quinlan, the woman in a coma. The

story was this: she was twenty, about my

age, at the time, and she had been raised in a loving home which is exactly

where I thought I had been raised. But

it seemed lately, as some articles alluded, she had become obsessed about

becoming someone, about doing something challenging. She had quit her job, quit numerous

jobs. Since graduating high school she

had gained weight, then lost weight. She

was worried that she wouldn’t accomplish anything. Her boyfriend had broken up with her. She had lately experimented with drugs. Valium seemed to be her drug of choice.

Here’s where Karen and I differed: I much

preferred amphetamines.

Both June and Hansen face their own mortality

with the news of Karen Ann Quinlan and a dying turtle that continues to be

washed ashore by the black Pacific beach.

After reading a newspaper article about Quinlan, the girls begin their

mission to search for the turtle, with hopes of bringing the sick turtle to a

turtle veterinarian. They are not able

to find the turtle, but Hansen is triumphant when she realizes there is one

thing she can do:

The most

important thing to me was to catalog it.

Even as we walked the beach I was thinking, I’ll remember this. June

said, I know you’re going to remember

this.

And then the El Mundo appeared, a white, low

castle in the darkness, the small neon sign flashing. The manager stood in the darkness on the

beach waving, the white sleeves of his jacket visible and rippling in the

moonlight, and telling us in Spanish what he had just heard – the turtle had

rescued itself and disappeared into the night.

The next morning Hansen and June read that the

New Jersey Supreme Court ruled in Karen Ann’s favor and they would pull the

plug, and she would finally be able to die in peace. That same morning the black waters of the

Pacific Ocean flooded into the cinder-block hotel and the girls go to the

manager’s door for towels and rags:

I was still cataloging things, trying to pin

them down, trying to test each moment for intelligence, or for a heartbeat, or

for its affect upon me – and then wondering if similar things had affected

Karen Quinlan similarly. And I did

remember it, his words to us as the ocean was rushing in and settling its sands

on the linoleum floor. I told them, he said, just to leave the floor of sand.

In “Lake Cumberland,” Hansen is now an

adult woman going to back to see a friend who suffers from schizophrenia, and faces the

extreme sadness that people change, and as a result, relationships can be lost:

In Chicago, where I first met her, where we

lived for a year, she was famous for being the model for a department store

that ran underwear ads in the weekend paper.

Then she worked for a steakhouse, and the manager, in some moment of

glad illumination, told her to run the bar,

mix drinks, have fun, just to be young.

It could be

I’ve conjured that image of her in the yellow

steakhouse shirt, running a couple of blocks in the rain with me because we

wanted suddenly to go and get drunk somewhere else.

It could be

Only the rain happened.

She lives now near Lake Cumberland because

she grew up there. Now, I knock on the

door. Now she runs a doggie daycare

business. Now I think of her hands and

wonder if they are the same.

In “There’s a Shoe on Your Plate” Hansen is an adult

woman, her grandmother (who used to be a ballroom dancer) has died, and she

reflects on one of the last visits she had with her grandmother in the nursing

home, sitting on her bed, both looking out the window at the trees dancing:

Nor should I recall following the shape of

her hands as she moved them to mimic trees outside. Her arms titled like branches.

Nor remember the words she said – Look, the trees are dancing.

Nor should I recall that I looked at the

trees beyond the wired window, beyond the curb of the parking lot and noticed,

sure enough, one could say they were dancing.

Sometimes the branches swayed in pairs.

Sometimes they dipped and caught each other. For this she hugged herself.

Soon two more people, the choreographer

with the shoe, and the orator join in with her grandmother in this trinity of

musical play:

I should not note that out in the hall across

from us, a man in a wheelchair had a tray of lunch in front of him and was

putting a shoe on his plate, and another man in a wheelchair across from him

was yelling. Don’t put your shoe on that plate.

Don’t put your shoe on that plate!

Nor should I further note that the first man

continued to arrange his shoe on his dinner plate. Taking a comb from his

pocket, he combed the laces carefully down each leathered side of the shoe and

pressed the tips of the laces into some lettuce, mayo, and tomato. The man who

had been yelling, now laughed and said, There’s

a shoe on your plate!

Excerpt from “There’s a Shoe on Your Plate”

It is the second to last stanza that Hansen

finally observes sadness and happiness mixed in with dementia and asks that

great question: is it possible to be

happy and face reality or must one

sacrifice one for the other?

And how ridiculous it would be to note this

momentary sadness, because no one there that day was sad. Certainly not the man arranging his shoe on

the plate, nor the grandmother staring out the wired window. And yet, there we were pinned – this

grandmother swaying, this granddaughter watching, this choreographer with a

shoe, while the other shouted, There’s a

shoe on your plate.

The collection ends with “She Has Given Me a

Spectacle and I Have Given Her a Pear” about Hansen’s mother who is recovering

from hip surgery. Mother and daughter

are able to communicate with one another over a Neiman Marcus catalog and a

simple pear.

She thanks me again for the pear. It is

the best pear, she says. What is your secret with pears?

Again I tell her again how easy it is to do

the pear. It seems, sometimes I can

count the things between us. One is –

this narration on the pear.

You let them ripen, I say, and then cool them they day before serving.

The one thing all of these poems have in common

besides memoir is nature, a haven for Hansen in her poetry, and a

responsibility she feels she owes to her readers.

“I am trying to create that world that is as momentary as

nature itself. Hence, at the wedding

scene there are “dresses flashing in the light of the open (tree) canopy.” I tend to use the senses, to write about

color – that old lover who wore the “Yellow steakhouse shirts,”

and still had that “halo of hair.” Writing this way, using color and smells, the

senses, allows for an immersive experience.

When I read I want to encounter more than just words, and more than tidy

cleverness, and more than well-explained themes. I’d like writing to lead to a real sense of

seeing the world, be it awful or lovely, through someone else’s eyes. As audience, I want to be more immersed the

way the writer was when he/she experienced it.

And as writer, I want to recall the phenomenal world for my

audience. It’s a tall order. I hope I achieved it in To Some Women I Have Known.”

Photograph

Description and Copyright Information

Photos

1, 21, 34, 37, and 40

Re’Lynn

Hansen

Copyright

granted by Re’Lynn Hansen

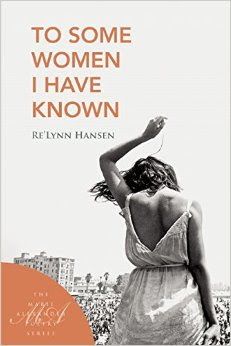

Photos

2, 7, 27, 32, and 35

Jacket

cover of To Some Women I Have Known

Photo

3a

Web

logo photo for Marie Alexander Series web page

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

3b

Web

logo photo for White Pine Press web page

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

4

Columbia

College

Attributed

to Re’Lynn Hansen

Copyright

granted by Re’Lynn Hansen

Photo

5

Two Hearts Beating As

One

Attributed

to Kari J Young

Copyright

granted by Kari J Young

Photo

6

Sappho Praying to

Aphrodite, After Margaritas

Attributed

to Chadwick & Spector

Photo

8

Notre

Dame de Chicago, built in Romanesque Revive Style

Attributed

to Andrew Jameson

CCASA 3.0 Unported

Photo

9

Wedding

Ceremony in the Chancel of Stanford Memorial Church, built in the Romanesque

Form

CC

By 2.0

Photo

10

Steps

to the Keep of Corisbrough Castle England

Attributed

to Richard Croft

CCBY

SA 2.0

Photo

11

The

Victorian Anne Queen House Ernest Hemmingway was born in

Oak

Park, Illinois

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

12

The Girl Writing in The

Pet Finch

Attributed

to Henriette Brown

Public

Domain

Photo

13

The End Of Dinner

Attributed

to Jules Alexandre Grun in 1913

Public

Domain

Photo

14

Whistlejacket

Attributed

to George Stubbs in 1762

National

Gallery of London

Public

Domain

Photo

15

Lady Godiva

Attributed

to John Collier in 1897

Herbert

Art Gallery & Museum

Public

Domain

Photo

17

At the Death Bed

Attributed

to Samal Joensen Mikines in 1940

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

18

Patty

Hearst graduation photo

Public

Domain

Photo

19

Miguel

de Unamuno

1925

Public

Domain

Photo

20

Patty

Hearst as Tania, after being kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army.

Public

Domain

Photo

22a

William

Faulkner

Public

Domain

Photo

22b

Ezra

Pound

Public

Domain

Photo

22c

Richard

Wright

Public

Domain

Photo

22d

Marguerite

Duras

Public

Domain

Photo

22e

Jacket

cover of The Lover

Public

Domain

Photo

23

Chapbook

jacket cover 25 Sightings of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker

Photo

24

First

photograph ever taken of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker

Attributed

to Doc Allen

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

25

Karen

Ann Quinlan’s high school graduation photo

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

26

Newsweek cover featuring Karen

Ann Quinlan

November

1975 issue

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

28

The Turtle

Attributed

to Christal Rice Cooper

Copyright

granted Christal Rice Cooper

Photo

29

Timeline

of Karen Ann Quinlan’s New Jersey Court decision

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

30

Scenic

view near Re’Lynn Hansen’s Michigan home

Attributed

to Re’Lynn Hansen

Copyright

granted by Re’Lynn Hansen

Photo

31

View

of Lake Cumberland, Kentucky from the Wolf Creed Damn

Public

Domain

Photo

33

Scenic

view of trees

Attributed

to Re’Lynn Hansen

Copyright

granted by Re’Lynn Hansen

Photo

38

Three Pears

Oil

on canvas in 1878-1879

Attributed

to Paul Cezanne

Public

Domain

Photo

39

Neiman

Marcus cover

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

41.

Re’Lynn

(left) with her partner Doreen

Copyright

granted by Re’Lynn Hansen