Christal

Cooper

Excerpts

given copyright privilege by Ronny Someck, Robert Manaster, and White Pine

Press.

Ronny

Someck:

The Milk

Underground

On

September 15, 2015 White Pine Press published The Milk Underground by

Ronny Someck and translated by Hana Inbar and Robert Manaster.

The

Milk Underground

is the winner of the 2015 Cliff Becker Translation Prize.

Translators Robert Manastar and Hana Inbar write

in in their introduction of The Milk Underground, titled “The

Pajama-Iraqi Israeli Poet”:

“The poems throughout The Milk Underground give a cohesive

voice to Ronny Someck’s oeuvre in Israeli poetry. He is a bridge builder. He is of the East as well as West. In an interview he explains, “I’m not looking

for roots. I never lost them. Baghdad is the East and it is planted in the

garden of the mind next to the tree of the West. Two trees that are two languages, which is

the mixer of my mouth has turned into one language.”

A Patriotic Poem

I’m

a Pajama-Iraqi, my wife’s Romaman

And

our daughter the thief from Baghdad.

My

mother’s always boiling the Euphrates and Tigris,

My

sister learned to make Perushki from

her Russia

Mother-in-law

Our

friend, Morocco the Knife, stabs

Fish

from the shores of Norway

With

a fork of English steel.

We’re

all fired workers taken off the tower

We

were building in Babylon.

We’re

all rusty spears Don Quixote thrust

At

windmills.

We’re

all still shooting at gleaming stars

A

minute before they’re swallowed

By

the Milky Way.

Someck has published ten other volumes of

poetry, which have been translated in over 41 languages: Exile; Solo; Asphalt; Seven Lines on the Wonder of the Yarkon; Panther; Rice Paradise; Bloody Mary; The Revolution Drummer; Algeria; and Horse Power.

Exile

Solo

Asphalt

Seven Lines

Panther

Rice Paradise

Bloody Mary

Algir

Exile

Solo

Asphalt

Seven Lines

Panther

Rice Paradise

Bloody Mary

The Revolution Drummer

Algir

Horse Power

Someck, 65, was born in Baghdad in 1951,

and his family emigrated from Iraq to Israel in the early 1950s as second

generation Mizrahim (Jews from Africa and Asian – the “East”). Someck managed to succeed in Israeli

society without sacrificing his Mizrahniess identity despite the domination of

the Ashkenazim (Jews of European descent – the “West”).

His first love was basketball, which he played

competitively, but then something happened when he turned 16.

“I wrote my first poem

by chance. It was a note I sent to a girl classmate. I was 16 at the time, and

a second before sending the note, I tore it to pieces. Being a basketball

player at one of the youth groups of Maccabi Tel-Aviv, it seemed to me strange

that I would suddenly write a poem. Back

home I told myself: You’re an adolescent, and the poem you’ve written is just

one of the symptoms. But on that very day I wrote another poem, and yet another

one on the day after. It scared me. I hid the poems in an old shoebox and hoped

this temporary “disease” would go away. One day, when the shoebox started

overflowing, I decided to send two poems to two people I knew of. I sent the

first envelope to a poet I already admired, David Avidan. He answered

immediately with a very beautiful and moving letter. I sent the second envelope

to the literary editor of a very popular newspaper in Israel. I wrote to him

that I’m wearing shirt number 7 in a basketball team and that I write poems in

secret. I asked him to read the poem and tell me whether or not it was good. I

specified that the poem was meant for his eyes only.

For two weeks I didn’t get any answer. I was sure my poem was

bad and unworthy of a reply. But on the third week, to my astonishment, the

poem was printed on the very top of the literary section. I was embarrassed

(for I specifically asked not to have it printed). Yet I felt happy for

receiving “confirmation” that the poem was good. I was very confused. Then I raised my eyes and saw that instead of

“Ronny Somech” which was my name at the time, they wrote “Ronny Someck”. Rather

than being annoyed I felt the happiest person on earth. This way, I told

myself, no one would know it was me.

Two days later, during

the first basketball training session that followed, the coach pressed his

shoulder against mine and said to me, “There’s someone with a similar name to

yours who writes poems.” He said it in a “warning” tone, implying it was a good

thing it was someone else. Evidently in his mind, as well as in mine, there was

no connection between basketball and writing poems.

I went back to the

shoebox, took out all the poems and sent them to all newspapers under my new

name, and like the Cinderella story – all the poems were eventually printed.

When my tenth poem was

printed, my coach said to me in the middle of the training, “You know, Ronny,

the guy with the similar name to yours printed another poem this week.” And

after a timeout he added, “A beautiful poem.” I then told everyone it was

actually me, and from that moment my life on the basketball team got

complicated. Every time I held the ball for more than a second my teammates

used to call out at me: Pass the ball! What are you thinking of, a new line?”

This changed Someck’s life – he became a poet

and an avid reader of poetry. His poetic

influences are Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Wisława Szymborska, Seamus Heaney,

Fernando Pessoa, John Berryman, Jacques Prevert, Charles Baudelaire, Charles

Simic, Adonis, T.S. Eliot, Hayim Nachman Bialik, Yehuda Amichai, Amir Gilboa,

David Avidan, Yona Volach, Lea Goldberg.

He is also influenced by fiction writers

Fiodor Dostoyevsky and Antonio Skarmeta.

Romeck worked as a social guide for street gangs until 1976, when at the age of 23 his first book of poetry, Exile was published.

He studied Hebrew literature and

philosophy at Tel Aviv University, and drawing at the Avni Academy of Art.

He used both of his artistic abilities in

poetry and drawing by collaborating with his daughter Shirly, 24, on two

children’s books: The Laughter Button and Monkey Tough, Monkey Bluff.

Someck,

who also writes music, does not write drafts of his poems, but rather lets the

ideas cook in his brain until the final poem is finished and ready to appear on

the page.

“I see my head as an

oven of ideas. At a certain moment, when I feel the dish is ready and might

burn if left for another extra minute, I transfer it from the metaphoric oven

onto the page. But always during the writing something new comes in a word, a

line, or a period. Something that takes even me by surprise.”

The Milk Underground is divided into

three parts: The Introduction: The Pajama-Iraqi Israeli Poet; a section

consisting of 25 poems; Field Sentences: Nature Poems; Street Sentences: City

Poems; and biographies on the translators and Ronny Someck.

The poem that was the most compelling for

Someck to write is “Baghdad”.

“I was born there. A German doctor helped bring me into this

world at a Jewish Hospital. My nanny was an Arab girl. My parents brought me to

Israel when I was a baby and the “Black Box” of my memory is empty.

But there were my

parent’s stories about the cafe by the Tigris, about the smell of the fruits at

the Shugra Market and about singers like Farid El Atrash and Abd El Wabb . My

parents spoke Hebrew, and only my Grandfather followed Baghdad’s lifestyle. He

spoke broken Hebrew and he used to take me to a cafe where they played the

music of the Egyptian singer UM KULTHUM and served black coffee just like in

the cafe by the Tigris.

As for me, Baghdad

turned into a metaphor, into a place that existed only in my Grandfather’s

heart.

I felt as if I threw

Baghdad out of my life’s window, but during the Gulf war it came back knocking

at my door. I was sitting with a gas

mask, watching TV footage from Baghdad. In every shot I tried to place my

stroller, or put lipstick on my young mother’s lips, or see my father brushing

his fingers through his hair. And a moment later I saw this place destroyed.

At that moment I felt I

missed the place I was born in, I missed the eastern side of my life, and I

very much wanted to mix it into my west side story.”

Baghdad

With

the same chalk a policeman outlines a body in a crime scene

I

outline the borders of the city my life was shot into.

I

interrogate witnesses, extort out of their lips

Drops

of attack and imitate with hesitation the dance moves

Of

pita over a bowl of hummus.

When

they capture me, they’ll take a third off for good behavior

And

lock me up in the corridor of Salima Murad’s throat.

In

the prison’s kitchen, my mother would fry the fish her mother

Pulled

out of the river, and she’d tell about the word “fish”

Displayed

on a huge sign over the new restaurant’s door.

Whoever

dined there got a sliver of fish until

One

of the customers asked the owner to reduce

The

sign or enlarge the fish.

The

fish will prick his bones, will drown

The

hand that scrapes its scales.

Even

boiling oil on the interrogation pan

Wouldn’t

get an incriminating word out of its mouth.

The

memory’s an empty plate, scarred with a knife’s scratches

On

its skin

Language is very important to Someck – in The

Milk Underground each poem is presented in Hebrew on the left page and

English on the right.

“I write in Hebrew,

which expresses itself on many levels: The Bible on the one, army slang on the

other. It also adopted words from the various cultures that immigrated to

Israel during the last century, as well as from the Arabic language of our

neighbors. Yet, if King David arrived this weekend to Jerusalem, he’d

understand the language. The poet's job

is, perhaps, to be King David's travel guide.”

Someck

takes his job as poet very seriously and describes his job as poet in Israel to

that of the American pianist we see in American western movies.

“He puts his piano at

the corner of the saloon, which smells of gun-powder. He knows this saloon is

not a concert hall but perhaps it's the real place. For his safety he says:

"Don't shoot me, I'm only the pianist".”

Someck lives in Israel with his wife Liora and

their daughter Shirley where he teaches creative writing and literature and

leads creative writing workshops. He can be reached at someck@netvision.net.il

Photo

1

Ronny

Someck

Photo

2

White

Pine Press web logo

Photo

3

The

Milk Underground

Photo

4

Cliff

Becker

Photo

5

Robert

Manaster

Photo

6

Hana

Inbar

Photo

7

"Patriotic"

Poem in Hebrew

Photo

8

Jacket

covers of poetry books

Photo

9

1950s

Family Photo

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Photo

10

Ronny

Someck at age 16

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Photo

11a

Allen

Ginsberg

Attributed to Duk, Hans vann/ Aefo

CCASA 3.0 Netherlands.

Attributed to Duk, Hans vann/ Aefo

CCASA 3.0 Netherlands.

Photo 11b

Jack Kerouac

Navy Reserve Reenlistment Photo 1943

Public Domain

Navy Reserve Reenlistment Photo 1943

Public Domain

Photo 11c

Wisława Szymborska

GFDL 1.2

GFDL 1.2

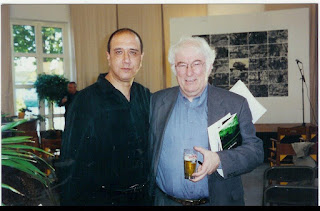

Photo 11d

Ronny Someck and Seamus Heaney

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Photo 11e

Fernando Pessoa in 1928

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo 11f

John Berryman

Attributed to Jerry Bauer

Fair Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Attributed to Jerry Bauer

Fair Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo 11g

Jacques Prevert

CCASA 1.0 Generic

CCASA 1.0 Generic

Photo 11h

Charles Baudelaire

Woodburytype portrait attributed to Etienne Cavat in 1862

Public Domain

Woodburytype portrait attributed to Etienne Cavat in 1862

Public Domain

Photo 11i

Charles Simic

GFDL 1.2

GFDL 1.2

Photo 11j

Adonis and Ronny Someck

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Photo 11k

T.S.

Eliot inn 1934

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo 11l

Hayim Nachman Bialik in 1923

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo 11m

Yehuda Amichai

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo 11n

Amir Gilboa

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo 11o

David Avidan

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo 11p

Yona

Volach

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo 11q

Lea Goldberg in 1946

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo 12a

Fiodor Dostoyevsky in 1872

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo 12s

Antonio Skarmeta

Photo 13

jacket cover of Exile

Photo

14

Ronny and daughter Shirley

Photo 15

The

Laughing Button

Photo

16

The

Monkey Tough, Monkey Bluff

Photo 17

Ronny Someck

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Ronny Someck

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Photo

18

The Milk Underground

Photo 19

Ronny Someck baby photo 1954

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Photo 20

Egyptian siger Um Kulthum in 1968

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo

21

Photo

of Grandfather Salah

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Photo

22

1955 Someck family, Ronny Someck in the middle.

Photo

23a

"Baghdad" in Hebrew

Photo 23b

Ronny Someck giving a poetry reading.

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Photo 23b

Ronny Someck giving a poetry reading.

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck

Photo

24

King David playing the harp

Attributed to Domenico Zampieri

Public Domain

Attributed to Domenico Zampieri

Public Domain

Photo 25

Painting Don't Shoot The Piano Player

Public Domain

Public Domain

Photo

26

Ronny Someck and wife Liora on their wedding day in 1985

Copyright granted by Ronnny Someck.

Ronny Someck and wife Liora on their wedding day in 1985

Copyright granted by Ronnny Someck.

Photo 27

Ronny and Liora Someck near Mezada in 2016

Copyright granted by Ronny Someck.