Christal

Cooper

Article/Excerpts

4,141 Words

The

Kashmiri Shawl by Joanne Dobson:

The Epiphanies &

Metamorphoses

of Anna Wheeler

Roundtree

She experienced the oddest sense of

having become two different souls inhabiting the same body, the timid writer of

inoffensive verses and emerging as from a cocoon a bolder more self-confident

literary woman

Excerpt from The Kashmiri Shawl

Page 125

Copyright granted by Joanne Dobson

Joanne Dobson’s first historical novel, The

Kashmiri Shawl, published by Cobb Hill Books, is 360 pages, each

individual page a page turner in every sense of the word: Heroine Anna Wheeler

Roundtree is a woman of many secrets who experiences numerous epiphanies and

metamorphoses throughout her 360-page life, the first of which is revealed

within the first five pages of the book.

Joanne Dobson first conceived the idea of The

Kashmiri Shawl in April of 1985.

Dobson had just completed her Ph.D. in American Literature and was in

the process of finding a position as an English Professor, when she came across

a National Geographic illustrated article on nineteenth-century

narrow-gauge Indian railroads, and, thus, Anna Wheeler Roundtree of The

Kashmiri Shawl was conceived.

“The scene came into my

imagination whole: a narrow, sooty, 19th-century steam-railroad

compartment somewhere in India. Anna rode, alone and terrified, fleeing her

husband and the mission compound where they lived. Just when she’s beginning to

feel she’s finally at a safe-enough distance from him, the train is ambushed by

a mob protesting British rule, burning and looting, killing Europeans. I

speed-wrote three or four pages, delighting in the myriad story possibilities.”

Nightfall was sudden as the train sped back

briefly into the jungle, then out into a mountain-enclosed valley. After an immeasurable time, Anna fell into a

muddled sleep, only to jerk awake when, from somewhere down the track came a

sudden crack of gunfire, then another, then a volley of shots. Heavy steps traversed the train’s footboards,

and porters shouted. A mob had destroyed

a railroad bridge directly ahead. Inside

the compartment, the air was thick with humidity and horror. Anna jumped up from her berth and brittle

specks of soot scattered to the floor.

And then the train jolted to an abrupt halt. Anna staggered, righted herself.

In the distance the engine chugged to no

effect. The steam whistle sounded once

again, a long, lamenting cry. Still the

train did not move. Shouts in the

distance. The howl of the mob. A line of torches advancing. Anna would die here, on this train, at the

hands of a people she had worked so hard to heal.

“Oh, my God,” Anna prayed aloud. “Send me to hell – I don’t care. Just let me live . . .” Her sobbing voice trailed off into an

inarticulate wail. Footsteps halted

abruptly on the boards outside her door, and someone tried to turn the handle

of the bolted door. It remained fast

shut.

“Are you English, Madam?” asked an urgent voice.

“American,” she responded, her heart now hoping.

“Open the door, the voice commanded.

Ands thus it was that Ashok Montgomery stood

there, outlined against the lurid light, aghast at the sight of her.

Excerpt from The Kashmiri Shawl

Page 173

Copyright granted by Joanne Dobson

“Then, almost immediately, I got a phone

call. Amherst College was offering me a

teaching job. The four-page scene went into a manila file folder, not to be

seen again for twenty years.”

In 2005, Dobson opened the manila file folder

again and began writing, this time she was also influenced by Charlotte Bronte’s

Jane

Eyre, the same novel she taught in her classes whenever she had the

chance.

She was particularly influenced, not by the

romantic Mr. Rochester, but by Jane’s other suitor, the missionary St John

Rivers. His marriage proposal to Jane doesn’t promise love, but requires duty. He

insists God made her to be a missionary wife, and therefore she should piously

labor by his side in the wilds of India.

“Jane turns him down.

Her reason is interesting: “If I were to marry you, you would kill me. You are

killing me now.” But she deflects the cause of her demise away from the man

himself and onto India: “I am convinced that go when and with whom I would, I

should not live long in that climate.”

I came away from my

reading of Jane Eyre with the

assumption that the Indian climate must be even deadlier than Jane’s would-be

husband. What, I asked myself in a frenzy of inspiration, would have happened

to Jane if she’d said yes to St. John Rivers and gone to India as his wife?

And thus was the second

birth of Anna Wheeler, missionary wife, fleeing her own “deadly” husband by

train through a lethal Indian landscape.

But though in Josiah’s eyes Anna does not

flourish as his wife, much less as a human being, she actually does flourish in

India – falling in love with the people, their land, their religion, their

customs, and even the country’s climate—and all of India falls in love with

her.

“Anna Wheeler thrives in

India. And so, too, with her intelligence, determination, and integrity might

have her inspiration, Jane Eyre.”

Having at last returned to New York, Anna

Wheeler Roundtree struggles to survive as a poet, barely making ends meet, only

able to afford renting a room at the unfashionable Manhattan house owned by

Mrs. Chapman.

It’s August of 1860 and Anna is in the

process of sharpening her quill with a penknife when she hears banging at her

door.

She is annoyed – part of the appeal of Mrs.

Chapman’s boarding house is its obscurity and isolation –so why would anyone be

pounding at her door? She tries to

ignore it but the pounding persists and she has no choice but to open the door,

to be is greeted by the young redhead Irish woman Bridget O’Neill.

Anna doesn’t recognize Bridget until Bridget

tells Anna that’s she’s a midwife. She also tells Anna something else . . .

“A

girl?” Something caught in Anna’s chest,

a fist on her heart. “A girl? And . . . crying?” She could still feel the coarse weave of the

birthing sheet between fingers cold and strained. “Bridey, you must be mistaken. Miss Parker said the infant never took a

breath.”

“And sure that lie has been on my soul

ever since that day. I’ve never seen a child so full of life. But it was just that--” She averted her gaze

as if about to address a most shameful issue.

“Well, Miss Parker and the housekeeper was all big-eyed, ye know –

hissing to each other in corners, like I didn’t have ears to hear.” Then she looked directly at Anna. “If I can speak plainly t’ye, Mrs. Wheeler,

from the looks on their faces ye’d of thought yourself had give birth to a

dog. But she was a pretty little thing,

that child. Looked me right in the eye

smart-like when I was washing her up.

Like she’d know me again if she seed me.

Soon’s I got her clean and wrapped, Miss Parker grabbed me arm and

dragged me into the back room. ‘Too bad

the child’s so poorly,’ she blathered.

And when I give her the fish eye, she pulls out her purse and pays me

off –double. ‘Far’s poor Mrs. Wheeler

knows, this child was born dead,’ she says, and stands n the front door and

watches me till I turn down Worth Street.

Later that night I was out to the grocery for . . . for a growler.” She cast Anna a sideways glance. “And I seen her slipping around the corner of

the Mission with a bundle clutched to her chest.” Bridey’s eyes were bright with meaning. “Just so.”

And she crossed her arms loosely as if she were cradling an infant. “And it were screetchin’ fit to beat the

band.”

“But –“

“Twas just, ye see, she couldn’t

understand it – and, mind ye, I’m not saying how it come about . . .” Her gaze left Anna’s face uneasily and

migrated to the beautiful Kashmiri shawl she clutched. “Ye see, I’m not one who

has a right to cast blame on any other woman – if ye understand what I’m about

saying. But somehow, for whatever

reason…” Her eyes snapped back to

Anna’s. “. . .that child was born a darky.”

Excerpt from The Kashmiri Shawl

Pages 5- 6

Copyright by Joanne Dobson

Anna, then, pursues her daughter, whom

she christens India Elizabeth, and it is through this search that her secret

love affair is revealed and her epiphanies and metamorphoses are experienced

and realized.

She also relives her past, that of being crushed

by her domineering and, now, supposedly dead husband Reverend Josiah Roundtree

for ten full years, while he led a mission in India.

To escape the domination of her husband, Anna

writes poetry in notebooks that she successfully hides from her husband in her

petticoat pocket. It is during one of

her husband’s sermons that she experiences another epiphany, not because of

what he preaches but because of a miraculous green lizard.

From outside came the familiar tweet

and trill of a bird, one she knew was small and green, but for which she had no

name. And with the sure and certain note

of that green song, something akin to a miracle came to pass in Anna’s soul: In the breathless air, between one pass of

the punkah and the next, a green

lizard jumped from the wall and flickered across the toe of Anna’s buttoned

boot, and it was as if all things changed, as if she had woken with a start from

a long, cold New England dream to find herself here in the midst of a life so

fecund it spoke not in the print on Josiah’s page, but in the scent of

bougainvillea, in birdsong.

She shuddered, cold and hot at the same

moment. She felt momentarily lifted out

of her body.

A lifetime’s doctrine drained from her

as wine might spill from a cast-off communion cup, only to be replaced by a new

revelation. Life! Here! Life!

Now! Life!

She had heard of Christians who had

lost their faith; now, in “the twinkling of an eye,” as the Bible said,

something equally cataclysmic had happened to her. She felt as if she’d been stunned by a

celestial hammer. It was all she could

do to keep herself seated in the pew, all she could do to keep from shouting

out: Life. Here.

Life. Now. Life.

It was as if her mind had leapt beyond

its education and entered a larger sphere.

As if she hadn’t lost faith, but had simply been liberated from icy dogma.

As if finally she knew what she’d been born to know: life was not simply some anxious, sin-fraught

anteroom to salvation or damnation; existence was itself salvation, warm and bright, throbbing with energy.

In that moment, after years of numb

obedience, she decided to leave Josiah, and the dry closed universe of his

world.

Excerpt from The Kashmiri Shawl

Pages 141 – 142

Copyright granted by Joanne Dobson

Anna escapes, but barely, the violent Indian

Rebellion in 1857, and finds herself impoverished living in that boarding house

in lower Manhattan where she writes voraciously in her three notebooks: one dedicated to poetry that only her religious

readers will read; the other dedicated to her experiences in India; and the

last dedicated to her innermost secrets and thoughts.

Anna is faced with a dilemma – to earn

some much-needed money, she must come up with 12 new poems within a month to

submit to Larkin & Bierce Publishers.

The only problem is she has no new “moral,” conventional poems; only

poems from her secret notebooks.

She would write only what poems she

knew she could sell to Larkin & Bierce.

But how could she possibly come up with a dozen within a month? She hesitated. Did she dare use the unguarded lines she had

written in India? No. Never.

But as soon as she wrapped herself

comfortably in Ashok’s shawl, his memory enfolded her. Covering the cherished wrap with a writer’s

smock against the inevitable ink stains, she began to write.

Simoom

As

murk as midnight is the sky, sultry and still the air.

Dust

flings death’s veil around them, the lost and wandering pair

She

looks at him with frightened eye. He

says, “We are together.

The

only storms to kill us now will be the heart – not weather.”

So

deep a darkness neither knew. They brave

it, hand in hand.

Until,

at last, deliverance viewed – the sun through floating sand.

The

song of bird is heard again. Heav’n’s

air restored to earth.

And

they who thought that they would die, now taste each other’s breath.

Even as she wrote, she understood that

this poem was not for Mr. Larkin.

Although – she must say – she doubted that the poor man would recognize

passion if he saw it. But, no, she could

not risk discovery; she set the poem aside.

At the moment Anna could do nothing

about finding her child. She must

concentrate on her poetry. Caroline was

going to ask Mrs. Fiske to make inquiries in the city’s African community.

Leaving her desk only for a few

fugitive hours of sleep and a snatched meal provided by Nancy, the Irish house

girl, she wrote for the next two days straight.

She wrote until her arm ached, her ink-stained fingers cramped around

the scratchy steel-nib pen, and the words swam upon her retinas. Eventually she did find herself plundering

the Indian notebooks – for monsoon, suttee, and creeping scorpion. For the savior of ginger, turmeric, and

cardamom. For images of jasmine and

languid evenings in the mountain air.

She wrote until she could write no

longer.

Excerpt from The Kashmiri Shawl

Page 87-88

Copyright granted by Joanne Dobson

Anna is just as obsessed and passionate about

her writing as she is about reading but due to her impoverished state she has

only four volumes of books: a three

volume edition of Jane Eyre; the blue cloth covered copy of Elizabeth Barrett

Browning’s poems; a dime copy of Charlotte Temple; and Leaves

of Grass by Walt Whitman.

She experiences another epiphany as she

stands in front of the Appleton Bookstore on Broadway. Even after she understands the cruelty she’s

experienced in her life and the damaging deception in the loss of her daughter,

Anna finds hope in books, particularly the expensive Lydia Sigourney’s poems

and Mrs. Southworth’s The Curse of Clifton.

She tries to resist the temptation of spending

her advance money from the publisher on books, but some force is driving

her to purchase these two books, and she does. Purchasing the books is more than a book

shopping spree, but permission to be independent, self sufficient, and to

recognize the power of words, even words that are not her own.

Stepping out of the shop with her

impulsive purchase added to her other parcels, she felt an energy radiating

into her, as if it were through the soles of her boots in their contact with

the sidewalk paving. At the corner of

Catherine Lane, with its mint sellers, buttermilk stands and hot corn vendors,

she purchased a paper cone of grapes and popped one in her mouth. For a moment she felt totally mindful of all

around her: the deep, rich hue of the

fruit, the stark lettering of the signs on the buildings, the rank smell of the

gutters, the cries of the vendors, the bold aspirations of the people. For a moment she saw herself not as an

isolated being, but as part of the teeming multitudes of this great city. For a moment, in spite of her fears for India

Elizabeth, she felt almost giddy with life.

Excerpt from The Kashmiri Shawl

Page 128

Copyright granted by Joanne Dobson

Anna searches for her daughter for

months, walking all over New York City, from Five Points, to Broadway, to the

East River waterfront, but she finds no sign of the child. Then she experiences another metamorphosis.

And, then one February morning, footsore,

Anna woke up to the tap-tap of small, mean snowflakes on her windowpane. Something had altered; Anna didn’t know

precisely what. She was stronger. It was as if steel had entered her soul as solid

as that framing Manhattan’s great new buildings. That day she ceased walking and, in her

clean, comfortable fourth-floor room, she began to write again.

She sat down at the cherry-wood desk,

and the lines that emerged from her pen she did not recognize as poems. They were not rhymed. Their meter was neither iambic nor trochaic

nor spondaic. The words flowed; they came out cold and bright, obdurate and

angry.

Thirty

long years, and countless spinning centuries,

Gabriel

shining by the bedside,

The

fear of being smothered in his wings.

It

seems there was a birth

And

swaddling clothes

Being

bound, or binding,

Shepherds

with uncomprehending eyes,

A

star and no lack of wise men

But

that was endless cycles of stars ago.

For

this nativity I am alone.

Anna recognized a new genius to her

work, but these were not pieces for Mr. Larkin or for Godey’s Ladies book. They were

neither inspirational nor comforting.

They were poems for herself, and she kept them to herself, hiding the

fragments of verse away in the secret compartment of the travel desk.

Excerpt from The Kashmiri Shawl

Pages 271-272

Copyright granted by Joanne Dobson

The greatest epiphanies and

metamorphosis - romantically, motherly, and poetically - Anna Wheeler Roundtree

experiences are bountiful and not shared in this article, in order to avoid

spoil alerts for would be readers.

Just like it took Anna Wheeler

Roundtree ten years to face the light and leave her husband, it took Joanne

Dobson ten years to finish The Kashmiri Shawl, a rare faceted

gem with lightning constantly running through its veins.

“Anna and I are both

born writers, and one thing we have in common is that it took each of us a long

time to realize that writing was a vocation as well as simply a talent. I write

because it’s what I want to do. I feel happiest when I have a writing project

going on. Anna, poor thing, writes out of desperation, both emotional and

financial. In some ways she writes for her life, and her writing saves her.

When she found a forgotten Indian diary full of poetic writings in her dresser

drawer, I almost shrieked for joy; I wasn’t expecting that!”

Dobson not only writes a compelling story

but also uses the real New York City of 1860s as its backdrop – no tourist

attractions are mentioned but only places that real New Yorkers would be aware

of, New York City at its most authentic.

Dobson, a New Yorker herself, accomplished this by intense research in

her own family of New Yorkers and New York archives.

“I did an enormous

amount of research for The Kashmiri

Shawl. My scholarly specialization is in 19th-century American

women’s literature, so I had a good jumping-off place.

Then I was granted a

Research Fellowship for Creative Writers at the wonderful American Antiquarian

Society in Worcester, Massachusetts.

For four weeks, I

immersed myself in their comprehensive collection of American books, magazines,

broadsides, posters, etc. I read original copies of 19th-century

books with titles such as Hindoo Life:

With Pictures (1866) and The

Mysteries and Miseries of the Great Metropolis (1874). After that delightful

plunge into the past, I had, of course, the Internet to fill in the gaps.

While I was doing

on-site research in New York, I felt like I was walking the streets of

Manhattan in two different centuries at the same time. I loved it! I’m a New

Yorker. I was born in Manhattan, raised in the Bronx until I was 12, when we

moved to Peekskill, New York. It’s a railroad town about 30 miles north of the

city (or The City. I always think of it capitalized!), so Manhattan was always

only an easy train ride away.”

Dobson completed the first draft of The

Kashmiri Shawl, originally titled The Missionary’s Wife, in 2009, but

she was not pleased, and the rough-draft manuscript lived in her filing cabinet

for several years.

It wasn’t until she was back at Amherst College

teaching a two-week course on Emily Dickinson that she rescued the manuscript from

her filing cabinet and began writing it again, this time with scissors,

staples, luck, and note cards.

“Alone, in

a small faculty-housing apartment, I literally (not philosophically)

deconstructed the manuscript tome—with scissors.

Taking it apart, scene-by-scene,

and stapling the pages of each scene together, I reduced the doorstop to a

multitude of variegated stapled sections.

Then, sucking in a deep, terrified breath, I tossed those sections high in the air and let them fall, higgledy-piggledy, all over the scarred maple dining-room table.

Once chaos—the true element of creation—was

Then, sucking in a deep, terrified breath, I tossed those sections high in the air and let them fall, higgledy-piggledy, all over the scarred maple dining-room table.

Once chaos—the true element of creation—was

achieved, I began to

make index cards briefly describing each scene, and attempted to organize those

cards into a completely new structure, with plot development and suspense in

mind. And the second incarnation of The Kashmiri Shawl began.”

It took her another two years to reach the final

editing process; but she still faced one dilemma: her character Satish Ghosh, Anna’s banian, who assists Anna in her search

for her daughter, would not come to life for her.

“On the page he was

paper-thin. Since the banian’s presence

was so very important to the crucial final chapters of the story, I was in

despair; I needed a character capable of guiding Anna through this vast alien

country.

Then, one day, I was

shopping at Target, when a short, plump Indian man caught my attention. He was

standing in the toiletries aisle studying the various brands of condoms,

picking the boxes up one by one, reading the descriptions. Finally he was down

to two particular brands, reading first the one package, then the other,

weighing them in his hands. Such scrupulous attention to detail … such

fussiness.

Yes! This was Satish

Ghosh! In my imagination, this stranger was whirled back to the mid-19th-century,

had five daughters, was desperate to provide dowries for them, and was … fussy.

At that moment he came alive for me—knowledgeable and scrupulously attentive to

detail, as well as fussy, but with a good heart, and I had a great deal of fun

writing him.”

“’The memsahib

without a soul.’ That is what the missionary wallahs are calling you,” Satish Ghosh, said, as he and Anna walked

in the garden of her Farrukhabad hotel. All around them oleander bushes hung

lush with clusters of pink and white blossoms and a delicate perfume suffused

the air. “Or so the kansamah at the Baptist Mission House is telling me he has heard as

he waits upon the dinner table.”

“Without a soul?” She frowned, perplexed,

then gave a short, bitter laugh. “Ah, a lost

soul!” The missionaries think I am a lost

soul! That must be what the butler heard.”

Satish looked at her sideways with his dark

eyes. “Soulful, I am thinking. Not soul-lost. Madame is filled with soul.”

She laughed again, this time without the

bitterness. “Thank you, Satish.” She smiled at him.

He looked astonished. Thanking me? For what, Madame?”

“You have just said a lovely thing.”

“Ah. I am meaning it.”

Excerpt from The Kashmiri Shawl

Page 329

Copyright granted by Joanne Dobson

Some readers might view Anna’s epiphanies and

metamorphoses as the abandonment of her Christian faith, but Dobson insists

that is not the case.

“I think

Anna has grown into a new understanding of Christian life, even if she might

not yet see it that way. She’s been traumatized by the institutionalized

Christianity of her childhood—a strict, literalistic Puritan dogma of fear and

hellfire. Rather than rejecting the teachings of Christ, however, the mature

Anna has evolved into a more transcendent understanding of Christianity as a

religion of love, compassion, and spiritual healing.”

Unlike most literary novels, The

Kashmiri Shawl has a happy ending – Anna in the end returns home triumphantly

– but that triumph is not complete – for there is still the battle against the

enemy that is never ending – the enemy being sexism and racism.

The only unfortunate thing about Joanne

Dobson’s The Kashmiri Shawl is that the same battle and the same enemies

are still being fought today.

Dobson presently lives in Brewster, New

York, which she described as quiet, woodsy, beautiful, and more country than

suburb. She commuted from Brewster to

New York City’s Fordham University for 20 years where she taught American

literature and Creative Writing.

Presently Dobson teaches fiction

writing at the Hudson Valley Writers’ Center, which is located right on the

Hudson River in Sleepy Hollow, the birthplace of American fiction.

Photograph

Description And Copyright Information

Photo

1

Joanne

Dobson

Copyright

granted by Joanne Dobson

Photo

2

Front

jacket cover of The Kashmiri Shawl

Photo

3

Back

jacket cover of The Kashmiri Shawl

Photo

5

Jacket

cover of National Geographic issue June 1984

Photo

6

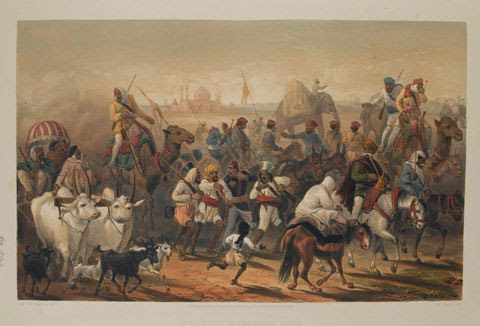

Troops of the Native Allies', 1857-1858 (c).

Coloured lithograph from 'The Campaign in India 1857-58', a

series of 26 coloured lithographs by William Simpson, E Walker and others,

after G F Atkinson, published by Day and Son, 1857-1858.

Although the Bengal Army rebelled during the Indian Mutiny

(1857-1859), the East India Company's Madras and Bombay Armies were relatively

unaffected and other regiments, including Sikhs, Punjabi Moslems and Gurkhas,

remained loyal, partly due to their fear of a return to Mughal rule. They also

had little in common with the Hindu sepoys of the Bengal Army. All three groups

helped capture Delhi and took part in its subsequent looting. They were helped

by the soldiers of those native states that opted to support the British. NAM

Accession Number

NAM. 1971-02-33-495-20 Copyright/Ownership

National Army Museum Copyright Location

National Army Museum, Study Collection

Public

Domain

Photo

7

Front

jacket cover of The Kashmiri Shawl

Photo 8

Photo

9a

Charlotte

Bronte

Public

Domain

Photo

9b

Three

volume edition of Jane Eyre

1847

2nd edition

Photo

10

St

John Rivers admits Jane to Moorehouse

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

11

Jane

turns down St. John Rivers’s marriage proposal

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law.

Photo

12

Jane

Eyre

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

13

Train

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

14

Chromolithograph

of Delhi, India published in The Illustrated News in November of

1857

Public

Domain

Photo

15

19th

century painting of woman with shawl

Public

Domain

Photo

16

The

kind of boarding house (hers is on Liberty Street) in which she hears momentous

news and begins her quest.

Public

Domain

Photo

18

19th

century quill and pen knife

Public

Domain

Photo

19

Jo, The Beautiful Irish

Girl

1860

Attributed

to Gustave Courbet

Public

Domain

Photo

20

Front

jacket cover of The Kashmiri Shawl

Photo 21a

The Epiphanies & Metamorphoses of Anna Wheeler Roundtree

Modeled by Janlyn Diggs

Photographed by Christal Rice Cooper

PHoto 21b

Wesleyan Mission Chapel in Bangalore, India in 1864

Attributed to J. Rozairio

Public Domain

Photo 21a

The Epiphanies & Metamorphoses of Anna Wheeler Roundtree

Modeled by Janlyn Diggs

Photographed by Christal Rice Cooper

PHoto 21b

Wesleyan Mission Chapel in Bangalore, India in 1864

Attributed to J. Rozairio

Public Domain

Photo

22

Lizard

– bronchocela cristatella

Public

Domain

Photo

23

Front

Jacket cover of The Kashmiri Shawl

Photo

24

19th

Century portrait of woman writing at desk

Public

Domain

Photo

25

Front

Jacket cover of The Kashmiri Shawl

Photo

26a

Three

volume edition of Jane Eyre

Public

Domain

Photo

26b

Jacket

cover of Poems Before Congress by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Photo

26c

Elizabeth

Barrett Browning

Public

Domain

Photo

26d

1814

Edition of Charlotte Temple

Photo

26e

Walt

Whitman (age 37) photo in the inside cover of Leaves of Grass

Public

Domain

Photo

26f

1883

Edition of Leaves of Grass with Walt Whitman on cover.

Photo

27a

Appleton’s

Building on Broadway belwo Grant Street

1860

Albumen

print

Photo

27b

Lydia

Sigourney (9/01/1791 - 06/10/1865)

Photo

by Matthew Brody

Photograph

taken somewhere between 1855-1865

Public

Domain

Photo

27c

Emma

Dorothy Eliza Nevitte Southworth

Quarter

plate daguerreotype in 1860

Public

Domain

Photo

27d

Jacket

cover of The Curse of Clifton

Photo

28

Front

jacket cover of The Kashmiri Shawl

Photo

29a

Five

Point sin 1859

Public

Domain

Photo

29b

1860

New York City Street Scene of Broadway looking north from Broome Street. The intersection in the center of the photo

is Spring Street.

Public

Domain

Photo

29c

Image

of the frozen East River from New York to Brooklyn

1871

Public

Domain

Photo

30

Front

jacket cover of The Kashmiri Shawl

Photo

31

19th

Century painting of woman with shawl

Public

Domain

Photo

32

Joanne

Dobson

Copyright

granted by Joanne Dobson

Photo

33

Image

of Ally Heathcote’s 1874 diary

Public

Domain

Photo

34

Joanne

Dobson’s mother, Mildred Abele, who worked as a private duty nurse in New York

City and left a treasure trove of letters she wrote to her family in Canada

about what it was like to live In Ne York City.

Copyright

granted by Joanne Dobson

Photo

36

The

American Antiquarian Society building in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Public

Domain

Photo

37a

Jacket

cover of Hindoo Life: With Pictures

Photo

37b

Jacket

cover of The Mysteries and Miseries of the Great Metropolis

Photo

38

1940s

or 1950s Photograph of woman walking in New York City

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law

Photo

44

19th

Century Painting of woman wearing a shawl.

Public

Domain

Photo

45

Sage Jajali is honoured by the Vaishya Tuladhara.

Attributed to Ramanarayanadatta astri Volume: 5 Publisher:

Photo 46

Photograph

of India in the 1860s

Public

Domain

Photo

47

India

man in 1860s photograph

Photo

48

Front

jacket cover of The Kashmiri Shawl

Photo

49

Joanne

Dobson

Copyright

granted by Joanne Dobson

Photo 50

The Spiritual Healing of Anna Wheeler Roundtree

Modeled by Janlynn Diggs

Photograph by Christal Rice Cooper

Photo 50

The Spiritual Healing of Anna Wheeler Roundtree

Modeled by Janlynn Diggs

Photograph by Christal Rice Cooper

Photo

51

Little

India Girl

Public

Domai

Photo

53

Joanne

Dobson

Copyright

granted by Joanne Dobson

Photo

54

Drawing

of The Hudson Valley Writer’s Center

Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law