Christal Cooper

Macy Halford:

My Utmost

A Devotional Memoir

“Finding Identity

Through The Little Black Dress of Books that can bridge the gap of two worlds”

Dallas, Texas native Macy Halford was

reared in a lifestyle of Timothy – without a father and depending on her mother

and grandmother for spiritual guidance.

I

am reminded of your sincere faith, which first lived in your grandmother Lois

and in your mother Eunice and, I am persuaded, now lives in you also.

--2

Timothy 1:5

She and her two younger siblings (brother

Preston and sister Alexandra) were reared by their grandmother, Marjorie Macy

Rutledge and mother, Deborah Rutledge-Hilkmann in the evangelical faith.

They attended the very conservative Southern

Baptist Church, The First Baptist Church of Dallas, every Sunday morning, Sunday

night, and Wednesday night where they would hear Pastor Wally Amos Criswell

preach from the Bible, something he did at the same church for 55 years.

They also reared her on the importance of

the Bible and the second most important book of all My Utmost For His Highest by Oswald Chambers.

Her grandmother, known as Nana, read the Utmost every morning and every

night. She told her granddaughter Macy

what made Utmost so good was because

it was real.

“Real?”

“Yes. You

know what I mean. It’s all about Jesus.”

“Is it?”

I said. This was curious to

me. “Isn’t it about

a

lot of things?”

To Macy, Utmost was more than just a book but also a ritual, a habit that

she witnessed both her mother and grandmother read every single night at 9 p.m.

I recalled the feeling, when I would spy on my mother

and my grandmother during their devotions, that the atmosphere in their

bedrooms was much altered from what it was at other times, and all because of

the fact that they had a certain book open on their knees and were locked into

it. Time slowed around them, grew

palpable. They grew powerful.

Girl With Basket of Plums attributed to Emile Munier

Macy’s first memory of Jesus Christ was

at the age of two when she learned how to sing this song:

I am a C

I am a C-H

I am a C-H-R-I-S-T-I-A-N

And I have C-H-R-I-S-T

In my H-E-A-R-T

And I will L-I-V-E-

E-T-E-R-N-A-L-L-Y.

As a young girl Macy had accepted Jesus as

Personal Lord and Savior and become saved, which according to the tenants of

the Southern Baptist faith, guaranteed her eternity in Heaven with the Trinity

God.

It wasn’t until she was 13 years old that

she was baptized, which Baptist teach is the first step of obedience after one

becomes saved. Her baptism experience

was not a good one since she wanted to be baptized in the church but succumbed

to the pressure of being baptized at church camp.

The

one night at church camp, a counselor had given me an ultimatum: either I would

agree to be baptized in the swimming pool with the other dawdlers, or I would

make peace with the fact that I’d been choosing against Jesus my entire life, and He knew it. I hadn’t heard logic like this expressed

before, but it was effective, and on Saturday night, beneath steady stars and

flickering neon lights, I was baptized. It was a stressful experience.

Matthew

3:13-17

The one highlight of that August night of 1992

was when her grandmother presented her with her first copy of My Utmost For His Highest.

Macy

explains further in an email interview dated April 11, 2017: “It was presented to me by my grandmother on

the occasion of my baptism, a rite that took place in a swimming pool in the

plains of East Texas. I remember shivering—it was cold for an August night—and

looking with blurred eyes as she extended her hand, saying she hoped the book

would guide me on my walk.

I’d taken the gift and

opened it, careful not to drip water on the pages. It was, I thought, the most

beautiful book I’d ever seen, slender and soft and covered in midnight-blue

leatherette, with gilded lettering that seemed to embody the dignity and mystery

of the title. At thirteen, I’d had an intense longing for these things—beauty,

mystery, dignity—but as yet had found few works that captured them.

That year, I read Wuthering Heights over and over, and

watched Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet

on repeat. To my unpracticed ears, the

ornate language of Utmost sounded nearly

Shakespearean (in fact, it belonged to the late-Victorian period, in which its

author had come of age).

For the next two years Utmost sat on her beside

table, until the summer she turned fifteen, the same summer she visited Paris,

France taking Utmost with her.

“I first started reading

My

Utmost for His Highest, the 1927 daily devotional by the Scottish

preacher Oswald Chambers, the summer I was fifteen and for many years I read it

aspirationally, believing that one day, when I was old enough, all its

mysteries would be revealed.”

It was The Book, the one I reached for

first, always, I used it in the way I knew many people at my church used it

(for it was from them that I’d first learned how to read Utmost, in a manner that

was close to praying), turning to it each day for a concentrated dose of

spirituality, meditating on its insights, committing them to memory.

At the age of eighteen, she moved to New

York, taking My Utmost with her.

There she attended Barnard College where she

majored in medieval history, graduating in 2000.

For the next four years she lived in New York

earning a living as a nanny until she got the job as copy editor for The New Yorker in October of 2004. She moved on to the Web department where she

wrote and edited a blog about fiction books.

Her life In New York made her realize how

different she was from her fundamental church, and other fundamental

Christians, not that they believed in different things, but because they deemed

intelligent thinking a direct contradiction to what the Bible taught. Macy believed the Bible taught one to think

outside the box, to question his or her faith, because it is through thinking

outside the box and questioning one’s faith that one’s relationship with the

Trinity God grows even stronger.

As a result Macy felt isolated from the

conservative political right and the conservative religious right.

The difference went all the way

down. I didn’t seem to think as these

Christians thought. Yet the difference

wasn’t total, and therein lay the dilemma.

I still recognized myself in my Southern Baptists – the earliest,

closest version of myself, the girl whose visions had fueled the adventure –

and when they prayed aloud, in a church service or a Bible study, I heard in

their prayers echoes of my own. Surely,

we were speaking the same God.

As a result, Macy found herself on a quest

of defining her identity, which had different layers and meanings. Her mother compared her to Esther, who hid

her Jewish heritage from her husband the King, but yet never abandoned her

Jewish heritage/family or denied her Jewish faith. Macy disagreed with her mother because she

felt Esther lived in a time where one’s culture and one’s honor to her God were

synonymous.

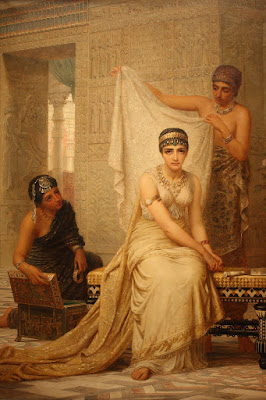

Esther Painting attributed to Edward Long

I’d been

taught early to turn to Scripture in moments of difficulty and had often found

sustenance there. But when I went

looking through the Bible for examples of people trying to perform the kind of

cultural tightrope walk that defined my adult life, no single hero or heroine

emerged.

Instead Macy found her identity in two

people Ruth and Orpah from the Book of Ruth, which tells the story of Naomi who

faces the death of her two sons. Naomi

gives her daughters-in-law Ruth and Orpah the choice of going back to their

families or staying with her. Orpah

chooses to go back to her family and Ruth chooses to remain by Naomi’s

side:

Whither

thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge:

Thy

people shall be my people, and thy God my God.

Where

thou diest, will I die, and there will I be buried”

The

Lord do so do me, and more also, if ought but death part there and me.

--Ruth

1:16

To me, it was Ruth and Orpah, two faces on

a two-faced coin. That coin was inside

me, turning and turning, and had been for a long time. Perhaps the issue would have resolved itself

had it ever been forced by external pressures, but although I lived (as all

Americans did) in the midst of a very old and ongoing culture war, it was generally

easy for me to avoid confrontation. This was the benefit, and perhaps the

curse, of living in a secular society in which freedom of religious expression

was both paramount and tricky to exercise – or rather to enjoy – in the common,

secular sphere. It was like a currency

one could not spend. Of my many friends

in New York who had grown up religious, there were only two who practiced now,

the rest having accepted the obvious: that it was extremely difficult to bridge

two warring worlds.

Her life took a turning point when her mother

insisted that she attend a women’s Christian publishing event at New York in

the Keens Steakhouse on West Thirty-sixth Street.

Macy was hoping to find more “kindred spirits” in

the group of Christian women but was confronted with ten women wearing red

blazers, gold-cross necklace, and tiny flag pins. She felt self-conscious with her head-to-toe

black attire, enormous horn rimmed glasses, plum lipstick, and frizzy French

style bun. She decided to keep her

“secular” job at The New Yorker a secret.

Then each woman was asked to give examples of

how the Lord blessed her on the job and how the Lord challenged her on the job. When it came to Macy’s turn she had no choice

but to reveal that she worked for the secular, sinful, non-Christian liberal

God forbid The New Yorker magazine.

‘How impressive.

“You must be the only Christian!”

“Why were they so mean about W?”

“You’re such an Esther!”

“They were mean, weren’t they!”

“How lucky we are to have you there!”

“How lucky we are to have you there!”

“That’s a Jewish magazine, isn’t it?”

Soon the leader of the group Rhonda asks Macy

if

she would recommend Christian material for her to read and she recommends My Utmost For His Highest. Rhonda tells Macy that Utmost is her favorite

book: “It’s like the little black dress

of books!”

After Rhonda reads a devotional from

September 14th to the small group of women she gives a mini sermon

on that devotional, where she urges to group of women that in order to be of

use to God one must be “spiritually real.”

Macy approaches Rhonda and asks her what she meant by “spiritually

real.”

“Oh, well you know real. It means that you’ve accepted Jesus as Lord

of all. That you trust Him totally,

instead of trusting the wisdom of the world.

Also that you’ve been tried and tested – that’s very important.”

“And how do you know if you’re real?”

“Oh, Macy,” she said sadly. She shook her head, “If you’re real, you just

know.”

We stood for a moment at the tope of the stairs.

“You should read Oswald,” she went on. “He’s very good on this question.”

As she is walking down the New York Street at night

she

remembers the comment her mother always made about Utmost, “The only people

who were real could understand it.” She

calls her mom on her cell and asks her mom what she meant.

Macy also confides in colleague Tom about

the events that happened at the ladies meeting and he gives her sound advice:

“Replace hypotheticals with facts. What’s the deal with this book? What do you know about the guy who wrote it,

about his context? Maybe you’re not the

one’s who reading him wrong.”

Macy takes her friend’s advice and

decides that she needs to go on this spiritual quest- to find out who Oswald

Chambers his, so she can find out more of who the Trinity God is, and have a

better understanding of who she is. She saves

enough money to last her six months, sublets her Queens apartment, quits her

job at The New Yorker and moves to Paris.

She resides in a boarding house in Paris,

located on the Fourth Arrondissement on the Boulevard Henry IV. Her room the brightest white consisting of a high

ceiling, twin mattress, large window, shower, an armoire, a desk, a sink, and

an old microwave oven.

It is here as well as at the Bibliotheque

Nationale de France, that she asks the important questions: Was Oswald a Baptist, an evangelical, Pentecostal,

Catholic, non denominational? What did

Oswald mean by the terms “actual” and “real” and what are the differences

between the two? How did Oswald manage

to balance his life as an artist/intellectual to that of the spiritual life focused

on Christ? How did Oswald view the Holy

Bible? How did Oswald view Satan and Hell? How much of Oswald is in the Utmost for His Highest or how much of it

is his widow Biddy? How did Oswald view

baptism? How did Oswald define the

Trinity of God? What was Oswald like?

And more personally how can she live a joyful

meaningful life without denying her love for Christ and denying her natural

born gift to think outside the box?

The process is studious, insidious, and

painstakingly intricate. She delves into

every single aspect of Oswald Chambers’ writings, which include over 50 books

and literally thousands of pages as well as research trips to Wheaton College

in Wheaton, Illinois; Discovery House in Grand Rapids, Michigan; the

Bibliotheque Nationale de France in Paris, France; and recollects on a previous

trip she took to Scotland in 2004.

Through her research she learns things

about Oswald that most people don’t even know.

In fact, most people think of My

Utmost For His Highest and Oswald Chambers as synonymous, which is far from

the truth. It is in these discoveries

that she learns the intricate, intimate, complex figure of Oswald

Chambers.

One of the most complex things about

Oswald Chambers is that he loved Jesus Christ, and believed that the expression

of this love and the expression of the Person Christ is not limited to strictly

germane spiritual realms – it could be found in literature, poetry, nature, and

even other people who were not Christians.

It is because of Oswald’s ability to see Christ, even in those who did

not believe in Him, that His love of Christ was so visual, inviting, and is the

supreme subject of My Utmost for His

Highest.

Utmost is truly a from of

spiritual art, and is not one specific person’s book bur rather the book

belongs to those who take the time to read the book, and go on his or her own

spiritual quest. We all will reach

different destinations and different views, but there are two things that cannot

be denied – Oswald’s love for Jesus Christ and the existent of Jesus Christ.

The most powerful excerpt from Utmost

is a conversation (similar to the conversation Jesus and Nicodemus had in John

3: 1-22) that Macy has with an unbeliever as they sit on top of the roof of the

boarding house, looking out onto the Paris skyline at night, drinking a cup of

wine.

“Oswald had these great ideas about God that were

so free, so freeing. He said that God worked through circumstances and that He

worked through chaos – what felt like chaos to us. He called it “haphazard order.’ It’s kind of a chaos-order that embraces all

possibilities, good and awful – even the ‘blackest facts.’ I guess on some level it sounds trite. You could say his philosophy was something

like ‘God moves in mysterious ways,’ or ‘God works everything together for the

good’ for the faithful, I mean, because that was a big part of it, this idea

that we never needed to worry about the chaos because God was working it all

out. When you study more what he’s

saying, you start to see why it’s so freeing.

When he talked about God’s order embracing all possibilities, he didn’t

mean only things like natural disasters and historic events, he meant

people. We, each of us, are unique

possibilities, none of us predetermined, each of us necessary – have you heard

the saying that it takes everything to make a world? It takes all of us to make God’s world, or rather

each of us. Oswald has this one sermon

about how there’s no such thing as ‘humanity,’ that God doesn’t make groups or

masses, He makes individuals, each one a ‘single, solitary life.’ That also might sound trite, but if you start

thinking about yourself as this haphazard collection of circumstance,

stretching back to the beginning of time, encompassing everything that

conspired to bring this thing into being, that is you, every event in every one

of your ancestors’ lives up to the point they procreated at least, every

variation in their always mutating DNA, you begin to understand that you’re as

vast as the universe, as incomprehensible and uncontainable as that. He said that personality was like the tip of

an island in the sea: the true

dimensions lie beneath the waves, too grand to be reckoned by anyone but

God. It was important for me, because it

meant that nothing in my immediate world had an ultimate claim over me. Those things had some claim, but not the

final claim. There’s only one authority,

Oswald said, and that’s Christ. Everything

else – your tribe or society or family or a church – is just collections of

individuals, each one the product of his or her own unique chaotic set of circumstances,

as indebted to the mystery as you are.”

“Wow,” the young man said. He sat up and poured more wine into the cups.

“Sorry,” I said.

“I’ve just been reading about him all night. All year.”

“Does it work?

This philosophy? You feel free?”

“Sometimes.

Not always. I think one reason

Oswald protested so much about groups and cultures and religions is that he

knew how powerful and eternal their grip on us was. He knew that on some very basic level we

needed frameworks and authorities. He

was about rebellion, not anarchy. But

I’ve never been a very good rebel. I

definitely don’t feel free from the pull of everything I grew up with. I’m not sure what I’d be without it. Mostly, I feel guilty when I think about

it. I fell guilty about not belonging to

a Southern Baptist church and not living at home. I feel guilty that I like what I like, and

not what my family wants me to like. I

even still feel guilty about not enjoying my baptism. But I’m not sure that’s the point.

“What’s the point?”

“I might not feel free,” I said, “but I am free. . . . ”

MACY

HALFORD now lives in Strasbourg, France, with her husband Thierry Artzner. She

teaches English at Sciences Po University and works as a freelance reviewer and

translator.