Christal

Cooper – 2,326 Words

Facebook

@ Christal Ann Rice Cooper

The Poet’s

Baptism of Memory and Experience

but we were not born to survive

only to live

The last two lines of “The River of Bees”

by W.S. Merwin

“ I guess

you could say I was baptized into poetry.”

Christina Lovin

This past month Christina Lovin, at least 50

years young, was appointed Senior Poet Laureate of Kentucky for her poem “Two.”

Being Senior Poet Laureate of Kentucky entails being a representation poet for

those at least 50 years old and older. Her poetry, aimed at this age bracket,

is beneficial for all generations, even today’s generation, to realize,

appreciate, and remember in order to have a productive life.

Memory and experience have always played

a roll in Lovin’s poetry, and life. Throughout her life, she has been creating

memories and depending on memories to live a life of a poet. Many of her

memories are those memories of herself as a child.

Lovin,

described her childhood as charmed and full of joy. Lovin is the youngest of

six living children reared by a father who was the game warden for Knox County,

Illinois, and a-stay-at-home-mom. Animals, nature, and people who loved her,

nurtured her during those early years.

Lovin’s

strongest memories are her memories of the women in her life. Her first vital

memory is of her grandmother Mary, who died at the age of 90, right after Lovin

celebrated her fourth birthday.

“I

distinctly remember visiting her in the country home (Knox County, Illinois). I

can still see the tall windows behind her bed and the light streaming in. She

gave me wintergreen lozenges that were thick, pink discs (wintergreen is still

my favorite flavor). When Grandmother passed away, I also remember her funeral.

In particular, I can visualize the maroon curtains with a stylized leaf pattern

that served as a divider between the general guests and those who were related.

The poem, “At Grandmother’s Funeral,” which appears on my website, pretty

accurately describes that day.”

Lovin remembers her mother singing hymns;

the same hymns that she heard while attending church. One of the hymns her

mother and the church would sing was “In The Garden,” the same hymn that was

sung at her grandmother’s funeral.

The women from her elementary school read

poems to the little girl: “I’m Hiding, I’m Hiding,” “Eletelephony,” and

numerous Emily Dickinson’s poems including “A Narrow Fellow in the Grass.”

Her environment played a huge role in her

development as a poet – being from Illinois she was very familiar with poet and

Spoon

River Anthology writer Edgar Lee Masters. When her family would visit

her uncle’s and aunt’s farm they had to travel over Spoon River.

“Spoon

River ran through the middle of their six hundred acre farm. I spent many hours

wading, swimming, and catching minnows and crawdads there. I guess you could

say I was baptized into poetry.”

Her journey through poetry included Edgar

Allen Poe’s “The Raven,” which she memorized when she was just a little girl.

When she was nine years old she was given

a box of small books, one of which held the

sonnets of William Shakespeare, which she also memorized. It was around the

same age that she started writing her own poetry, and, two years later, she had

her first poem published in the Young America Sings anthologies.

A few years later, the young teenager

purchased Best Loved Poems of the American People that was soon dog

marked, especially the pages that bore the poems of “Man With a Hoe” by Edwin

Markham, as well as female poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox. She was soon reading the

contemporary poets W.H Auden, Robert Frost and T.S. Eliot.

Her identity as a poet was not cemented until

adulthood, when, in the in the spring of 2000 she attended Harvard University’s

summer writing program, taught by Pulitzer and National Book Award finalist

Poet Bruce Smith.

“I

began to understand what real poetry looked and sounded like, while I began to

see that my life needed to change direction. At the end of the summer, one of

my poems, “North Side of the House,” appeared in the Harvard Summer Review, and

I was on my way to serious writing.”

She continued other summer writing

courses at Harvard in the summer of 2001 where Bruce Smith and fiction writer

Jody Lisberger, her instructors, encouraged her to enroll in a Master of Fine

Arts program, which she pursued at New England College in January of 2002, with

Li-Young Lee as her faculty mentor. It wasn’t until 2004, just before

graduation, that she finally felt she could call herself poet.

“The

Senior class had a reading, with each of us reading for about twenty minutes. As

I sat down after my reading, a very famous poet, Michael Waters, leaned forward

from his seat behind me and whispered, “Line for line, not a word was wasted.”

Then after the reading, one of the other students came up to me, shook my hand,

and said one word: “Poet.” That was the moment I really felt that I had

something to share through poetry. I don’t consider my career to be poetry, but

I do consider myself a poet. Like any art, some levels of skill can be taught

to just about anyone, but unless that spark is there, he or she will not be an

artist or a poet.”

She continued to grow as a poet as writer-in-residence

for numerous art colonies: Carl Sandburg’s home Connemara, located just outside

Flat Rock, North Carolina; Andrew’s Experimental Forest, located on the western

face of the Cascade Mountains near Blue River, Oregon; Devil’s Tower National

Monument, located in the Black Hills of southwestern Wyoming; the Footpath’s

House to Creativity, located on the Island of Flores in the Azores archipelago;

Vermont Studio Center, located in Johnson, Vermont, near the Canadian border; Virginia

Center for the Creative Arts, located near Sweet Briar College, outside

Lynchburg, Virginia; Prairie Center for the Arts, located in Peoria, Illinois;

and the Hopscotch House, a 10-acre farmstead located 13 miles east of downtown

Louisville, Kentucky.

“What is most important

to me about these experiences (including teaching creative writing) is the

connection with other writers. I remember reading once that writers and poets

are a “tribe.” I felt so relieved to know and understand that I had a tribe—people

who, like me, live and work differently than people who are not artists. I also

have to add that getting to know many visual artists has been an incredible

experience. Although we approach our art(s) differently, we respect and honor

the others’ sensibilities. I’ve found that visual artists are more upbeat and

industrious, while writers/poets tend to be more morose and solitary. It’s

always good to have a mix of these people when they are thrown together for a

month or longer.”

Lovin felt a connection with Sandburg on

numerous levels: both are poets; both shared a Swedish heritage; and

both come from Galesburg, Illinois.

“It was a great

experience. Being in the main house, which has been left just as it was when

the Sandburg’s lived there, was incredible.”

During her stay at Andrew’s Experimental Forest,

Lovin visited six “reflection spots” throughout the forest; and then wrote

about her thoughts, one of which was a poem about her experiences there titled

“Two,” the same poem that won her the title of Senior Poet Laureate, Kentucky.

Lovin spent a week as writer-in-residence at

Devil’s Tower National Monument. She drove to the huge monolith during the

nighttime, not able to see the monolith but able to fell its presence.

“The next morning, it was right where I knew

it had to be. I only wrote one poem while I was there (“Little Fires”).

However, after watching the tower at different times of day and night, it

reminded me so much of Monet’s paintings of haystacks and Rouen Cathedral that

I wrote a fictional sestina, “Monet’s Diary,” which reflects on how he might

have viewed the monument.”

Lovin spent a month at the Footpaths House to

Creativity, with no television or easily accessed Internet, which disciplined her

to spend her entire stay writing, reading, and exploring the area.

“I read a dozen books, including many novels,

and the nonfiction crime novel, In Cold

Blood, which has made me a huge Truman Capote fan. I spent a lot of time in

the sunroom of Casa em Pedra (house of stone), looking out at the Atlantic

Ocean below me. It was a magical time.”

She spent four weeks at the Vermont Studio

Center, where she experienced artists of all genres; some who have become dear

friends.

“I’ve had the

opportunity to study briefly with poets such as Anne Waldman, Marie Howe, and

others. Always a productive time spent writing alone in a lovely writing

studio, as well as socializing with others at dinners, social events, readings,

and open studios.”

Her most recent residency was at Virginia Center

for the Creative Arts, this past March.

“ I’ve had residencies

at VCCA on three occasions. I’ve been there in the summer, winter, and now the

spring. The groups at VCCA are much smaller than VSC, with there being only

around twenty fellows in residency at any given time. Once when I was there,

there were a number of singer/songwriters in residence, and I had the good

fortune to spend time with and get to know country music star, Kathy Mattea and

her husband, Jon.”

The Prairie Center for the Arts residency is Lovin’s

favorite because it is in the area of Illinois where she grew up and spent most

of her adulthood. Thus far she’s had four residencies there and will return for

another residency this December.

The Hopscotch House, a farmhouse, is owned and

run by the Kentucky Foundation for Women.

“Except for the lights

of town, one would think he or she was far out in the boonies. It’s a lovely

farmhouse with beautiful rooms and a wonderful kitchen to create communal

meals. One of my favorite memories is being there with several women writers

from my area of Kentucky, one of whom passed away two years ago.”

When

not writer-in-residence at numerous locations, Lovin is a full-time lecturer at

Eastern Kentucky University; her one consistent course she has taught since

2010 is the Introduction to Creative Writing. She considers her position as a

lecturer not only to teach but also to help students, especially those who want

to be writers, to incorporate creative writing in their professional and

personal lives.

“I’ve had some students who began submitting and publishing

pieces even before the semester was over. It’s exciting to find students who

are obviously going to do well in the creative writing field, then encourage

and mentor them as they move forward. Who could ask for more from a job?”

Unlike most poets, Lovin does not have a

specific routine, does not write every single day, and is not prolific.

“I’m

always amazed that some poets write a poem each day – I could never do that. I

tend more to write in “clumps” of time and energy, then maybe not find the

inspiration to write again for days or weeks. Inspiration comes when something

inside a writer (spirit, sensibility, whatever one would like to call it)

interacts with something outside (an image, an event, a connection).”

When the muse comes to her it usually begins with

an image, word or phrase, which she immediately writes on a piece of paper. Later,

when another image or thought comes to her, she’ll write it down, and revise

the first notes and work on it until a poem is formed. Sometimes this process

can take years between the first set of notes to the final draft of the poem.

Other

times the muse will hit at the most inopportune times – while driving. She was

driving through the Smokey Mountains, inspired by a motorcyclist on the road

ahead, when the muse hit. She dialed her own cell phone number and left herself

a message with the draft of the poem – the result is the poem “The Zen of

Mountain Driving.”

“I’ve done this many times.

There is something about driving that seems to free up my mind for poetry.”

The one thing she does do daily is read,

which she believes is necessary in order to write effectively. In the process

of reading, she’s discovered poems that have made her life more productive, or

changed her life in a positive way. Some of the poems that have changed her as

a person for the better are W.S. Merwin’s “The River of Bees”; “Love After

Love” by Derek Walcott; “This Room and Everything In It” by Li-Young Lee; “Behaving

Like A Jew” by Gerald Stern; “Facing It” by Yusef Komunyakaa; “Manifesto: The

Mad Farmer Liberation Front” by Wendell Berry; “Our Love Is Like Byzantium” by

Henrik Nordbrandt; “Places Propituous for Love” by Angel Gonzales; “Things I

Didn’t Know I Loved” by Nazim Hikmet; and “Dulce et Decorum East” by Brit

Wilfred Owen; and Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman.

“There is no one reason

these particular poems moved or changed me, but they did. There was an

emotional connection between myself and the poet, which is where I believe art

becomes art (not when the poet writes the work.”

Lovin is

thrilled to be Senior Poet Laureate for Kentucky and already has a poetic

connection with those she is to represent and her entire community. Lovin

believes part of being a poet is to be able to connect with the reader.

“I guess for me, poetry must elicit a response

in the reader or listening, regardless of the form, language, and skill of the

writer.”

Her poem “Two,” in addition to her other poems,

are examples of this response from reader and connection between reader and

poet.

For more information visit her website www.christinalovin.com to read her poetry, to email Lovin,

click on the “Contact Me” link there.

PHOTO DESCRIPTION AND COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Photo 1

Christina Lovin.

Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 2a.

Big Brother Darrel and baby Christina. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 2b.

Darrel, Kent, and Christian.

1951. Copyright by Christina

Lovin.

Photo 3a.

Bob and Clara Ericson on their wedding day. August of 1925. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 3b.

Bob and Clara Erickson in 1925.

Photo 3c.

Christina Lovin’s father Bob Ericson. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 3d.

Christina Lovin’s mother Clara Ericson at age 33. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 3e.

Ericson Family.

Christina Lovin far right. 1965.

Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 4.

Christina Lovin, around age 4. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 5.

Grandma Mary.

Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 6a.

Christina Lovin, age 6, with her mother. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 6b.

Clara, sitting down, with Christina standing next to her,

far right. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 7a.

Emily Dickinson at Mount Holyoke in 1847. Public Domain.

Photo 7b.

Christina Lovin, far left.

Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 8.

Spoon River Anthology jacket cover.

Photo 9.

Edgar Lee Masters Postage Stamp. Public Domain.

Photo 10.a.

Spoon River in Fulton County, Illinois. Attributed to United States National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration. Public

Domain.

Photo 10b

Christina Loving with her horse. 1964.

Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 11.

Edgar Allan Poe in November 9, 1848. Attributed to Edwin Manchester. Public Domain.

Photo 12.

Illustration for “The Raven” in 1858. Attributed to John Tenniel. Public Domain.

Photo 13.

William Shakespeare in 1810.

Attributed to John Taylor. Public

Domain.

Photo 14.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets jacket cover in 1609.

Photo 15.

Edwin Markham in 1919.

Attributed to Jonn B Homer.

Public Domain.

Photo 16.

Ella Wheeler Wilcox in 1908.

Public Domain.

Photo 17.

W.H. Auden in 1939.

Public Domain.

Photo 18.

Robert Frost in 1941.

Photo donated from New York World Telegram & Sun Collection to

Library Of Congress. Public Domain.

Photo 19,

T.S. Eliot in 1923.

Attributed to Lady Morrell.

Public Domain.

Photo 20.

Bruce Smith at the Lannan Center in Georgetown University

October 2, 2012. Attributed to

SlowKing4. GNU Free Documentation

License 1.2.

Photo 22.

LI-Young Lee.

Copyright by Li-Young Lee.

Photo 24.

Connemara. Copyright

by Christina Lovin.

Photo 25.

Andrew’s Experimental Forest, Lookout Creek. Attributed to Tom Araci. Public Domain.

Photo 26.

Devil’s Tower National Monument. Attributed to Christina Lovin. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 27.

Casa

em Pedra. My home for four weeks. The square room to the left is a wonderful

sunroom with doors all around. I spent most of my time there. — in Lajes das Flores, Azores, Portugal.

Photo 28.

Vermont Studio Center’s Maverick Studio overlooking the

Gihan River. Copyright by Christina

Lovin.

Photo 29.

Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Lovin’s studio is the third window from the

left. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 30.

Prairie Center For The Arts logo. http://www.prairecenterofthearts.blogspot.com

Photo 31.

Hopscotch House.

Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 32.

Christina Lovin.

Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 33.

Carl Sandburg in 1955.

Attributed to Al Ravenna on behalf of donated to Library of Congress.

Photo 34.

The Farm Manager’s Cottage at Carl Sandburg’s home

Connemara. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 35

Rock Formation at Andrew’s Experimental Forest. Public Domain.

Photo 36.

Christina Lovin at the Devil’s Tower National Monument. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 37.

Claude Monet in 1899.

Public Domain.

Photo 38.

Claude Monet’s Haystacks.

Oil on Canvas. Public Domain.

Photo 39.

Claude Monet’s Rouen Cathedral. Public Domain.

Photo 40.

Footpath’s House to Creativity. Christina Lovin overlooking Cedres. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 41.

Truman Capote.

Creative Commons Share Attribution Alike

Photo 42.

In Cold Blood jacket cover.

Photo 43.

View from Prospect Rock at Vermont Studio Center. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 44.

Anne Waldman in 2003.

Attributed to Gloria Graham.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Photo 45.

Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Cows

grazing with Sweet Briar College in the background. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 46.

Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 47.

Hopscotch House – Christina’s bedroom. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 48.

Christina Lovin.

Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 49.

Christina Lovin giving a poet reading. Copyright by Christina Lovin.m

Photo 50.

Christina Lovin at the AWP 2012 Conference. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 51.

Christina Lovin.

Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 52.

Christina Lovin standing in front of her car in 1976. Copyright by Christina Lovin.

Photo 53.

Derek Walcot in Amsterdam May 20, 2008. Attributed to Bert Nienhuis. GNU Free Documentation License 1.2 or later

version.

Photo 54.

Li-Young Lee.

Copyright by Li-Young Lee.

Photo 55.

Gerald Stern at the Miami Book Fair International on

November 19, 2011. Attributed to Rodrigo

Fernandez. Creative Commons

Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

Photo 56.

Yusef Komunyakaa at the National Bok Critics Circle Awards

of 2011. Attributed to David

Shankbone. Creative Commons

Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

Photo 57.

Wendell Berry on July 27, 2007. Attributed to David Marshall. Creative Common Attribution-Share Alike 2.0

Generic License.

Photo 58.

Nazim Hikmer. Fair

Use Under the United States Copyright Law.

Photo 59.

Walt Whitman in 1887.

Attributed to George C Cox.

Restoration of photo attributed to Adam Cuerden. Public Domain.

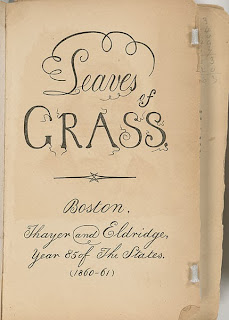

Photo 60.

Leaves of Grass jacket cover 1860 – 1861.

Photo 61.

A Stirring In The Dark jacket

cover. Old Seventy Creek Press (http://old-seventy-creek-press.com)

Photo 62.

Flesh jacket cover. Finishing Line Press (www.finishinglinepress.com)

Photo 63.

What We Burned For Warmth jacket

cover. Finishing Line Press (www.finishinglinepress.com)

Photo 64.

Little Fires (New Women’s Voices, No. 55

jacket cover. Finishing Line Press (www.finishinglinepress.com)

Photo 65.

Christina Lovin and Carl Sandburg’s goat. Copyrigh