Christal Cooper

GUEST BLOGGER:

William Sanders and His Memoir

Staying A Multi-Generational Memoir of

Rescue and Restoration

I am married and my wife and I have two (almost) grown

daughters.

I spent 20 years as a writer and editor at daily

newspapers, the last 12 of which were with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

I won various state and regional writing and reporting contests, both as a

sports writer and a features writer.

I

sat down one evening and started writing my story. The problem was, I didn’t

know a lot about my early childhood and some events that forever shaped my

life. Our family kept secrets buried away so we wouldn’t have to deal with

them. That was the way things were in the 70s, and my dad carried that through

the decades.

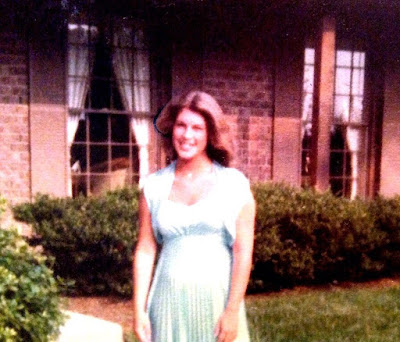

Cindy's high school prom

And Cindy (older sister) and I respected him, and his heroics, enough that we never asked him to open up and tell us what really went on in the years of 1971-73. When I started writing, I didn’t expect him to be as forthcoming as he was. Nor did I expect to find others who I hadn’t seen in 40 years to surface. All of a sudden, I had material for a memoir.

Cindy's high school prom

And Cindy (older sister) and I respected him, and his heroics, enough that we never asked him to open up and tell us what really went on in the years of 1971-73. When I started writing, I didn’t expect him to be as forthcoming as he was. Nor did I expect to find others who I hadn’t seen in 40 years to surface. All of a sudden, I had material for a memoir.

My

memoir Staying A Multi-Generational Memoir of Rescue and Restoration was published by Heart Quest

Publishing on June 9, 2015.

Lauded by TrueFaced's John Lynch, bestselling author and fellow Atlantan Jeff Foxworthy, bestselling author Andrew Farley and Third Day lead

singer Mac Powell, Staying A Multi-Generational Memoir of

Rescue and Restoration is a memoir of hope, faith and love, but

it is full of gritty and authentic moments every parent will find relatable.

John Lynch

Jeff Foxworthy

Andrew Farley

Mac Powell

I recall, "Sitting

in the backseat of a car driven by my abductor, a crazy woman I used to call

mom, the six-year-old me pleads for something I had no expectation of getting.

Mercy.

Sitting beside me is

eight-year-old Cindy, my sister, comforter and fellow victim of a plot that

would forever shape the course of our lives. She whispers to me that things are

going to be okay. I guess in the longest of long runs, she was right.”

Cindy

and I have always been close, particularly after we both started families. We

did then, and still do, talk two or three times a week, about things that

matter or about things that don’t, like the TV show we watched the night

before. She lives five hours away. But even when she lived 10 minutes a way,

ours has been more of a phone relationship, often during my long commute to or

from work. We rarely talked about our past – maybe once or twice a year. When I

decided to write the book, she was on board and encouraged me throughout. She

told me things that she’d experienced that I cannot believe she hadn’t told me

in the 30 years of our adulthood.

John Lynch and William Sanders

August 1971

I

|

t is my first memory of attempting to control an

uncontrollable situation. I have just turned six years old, and I’m not yet

good at controlling much of anything, particularly something that is rocking my

fragile heart and scaring me in a way that I’d never known.

I

don’t remember any specifics about life before this day, August 5, 1971.

Actually, I don’t even remember how this day started, or exactly how I had

found myself in the backseat of this car, sitting next to my sister Cindy, who

is about to turn nine years old, and who is far too young for what is about to

be asked of her.

“Let us go home and pack something,” I said to

my mom, who had disappeared until today almost a year earlier. “Or we can do

this another time. Just take us back home, and we’ll figure it out from there.”

Those may not have been my exact words,

but tearfully, that is the exact case I’m making for why Cindy and I should not

be kidnapped. Of course, I have not rehearsed for such a situation, so I’m

neither convincing nor effective. It’s also the first time I remember failing.

“Oh no, Bill. We ARE going to the airport

and we ARE going to Tampa. Today. Now,” said Charlotte, from the driver’s seat,

with her mother, a weak, small browbeaten woman sitting in the passenger seat

next to her.

It takes 45 minutes to drive from Nana and

Pop’s house to the Atlanta airport. Cindy and I had lived with my grandparents

and my dad now. About six months ago, while Dad was at work one day, my mom had

dropped us off at a neighbor’s house one morning and left. She’d made the same

drive to the same airport all alone, gotten on the same plane to the same city

and out of our lives for what all I knew would be forever.

This was the first time I’d seen her

since.

Now she’s driving me away from whatever

semblance of security and innocence I had been clinging to the last half year.

I’d been abandoned way too recently to have the level of security and innocence

a little boy should have.

But with every passing mile on Interstate

75 and then Interstate 85, and then with the 500 miles through the air, we’re

getting so far away I’m not at all sure that I’ll ever be able to fully find my

way back. Mommy is taking us headfirst into a lifetime of fear with the windows

rolled down.

This is not an ugly custody squabble

playing out. It is not a case of a good mother who would go to any extreme to

be with her kids, even if it meant skirting the rules or the laws. Of course I

couldn’t verbalize it then, but on some level I know, even at this tender age,

that the backseat of this car traveling down the highway is ground zero in a

battle of good versus evil.

This is more akin to abduction by a

stranger. I recognize this woman as my mom, but I don’t really know her. I

certainly don’t know what she is capable of and I don’t have a single memory of

her ever acting motherly.

So while I probably don’t even know what

kidnapping means, I know with as much certainty as a 6-year-old boy can have

that I am in trouble. There is no way Nana and Pop, or especially Dad, would be

OK with this. And neither am I.

I cry on the way to Atlanta’s Hartsfield

International Airport. Cindy does not. Instead, she is doing what the older

sibling is supposed to do in the midst of chaos and crisis. She is trying to

comfort me.

“It’s gonna be fine, Bill,” she says, at

first talking loud enough for Charlotte to hear. “We’ll get on an airplane, go

to Florida and be home before the weekend is over.”

Then, quieter, almost whispering and only

for me to hear, she says it again.

“We’ll be OK. It’s our mom. We’ll be OK.”

This is Cindy’s first crack at telling a

lie for the sole purpose of making someone else feel hopeful. And like my first

attempt at controlling a situation, it’s not working.

“We’ll get there and you’ll see that it’s

not so bad,” the woman formerly known as my mom says. I’m not sure if she quit

being mom when she first left us, or whether it was sometime over the ensuing

six months, or if it happened 20 minutes ago. “We’re calling your Nana to tell

her the plans. She won’t mind. Neither will your dad.”

“Liar,” I think to myself but don’t dare

say out loud. For that one moment, I was equal parts scared for myself and mad

that she would say that and expect us to believe it.

“We’re staying with Mary Ellen at her

apartment. You remember Mary Ellen. She adores you and Cindy. And there’s a

beach in Tampa.”

Mary Ellen. I’m no longer equal parts mad

and scared. I’m 100 percent scared again.

“Can we go back home first?” I asked.

“No, we’ve got to get to the airport.”

“When are we coming back home?”

“We’ll see.”

Charlotte’s mother, “Gan” to Cindy and me,

keeps quiet.

As we walk through the Atlanta airport, I

think about finding a policeman and running to him. But I don’t. That takes

courage, and right now, for the first time, I can tell that I don’t have it.

We make our way through the airport

terminal without a scene. We get on a plane and two hours later, we are in

Tampa. Tampa might as well have been Tokyo. Or Mars. It’s that distant and

unknown to me.

The

woman formerly known as my mom, Charlotte, is beauty queen material with blonde

hair and a charming first look. As promised, this beauty queen drives us

straight to Mary Ellen’s apartment. Mary Ellen is a short, stumpy,

frizzy-haired woman, with Brillo-like hair, and is not a beauty queen in

anyone’s pageant. I think she is somewhat familiar to me, which is to say I

recognize her, but not much more. But she will become a major player in our

story. And despite what my mom had just told us, she certainly doesn’t adore

Cindy or me.

Also as promised, Gan calls Nana.

Of course I didn’t hear the call, but I’ve

been told it was short: “Era, Charlotte has taken the kids to Tampa. They

belong with their mother.”

What kind of grandmother aids and abets

such a bold abduction? By all accounts, she’s neither a bad person nor a strong

one. Perhaps she’s under duress herself. Maybe she’s seen enough in her own

daughter to not want to be on her bad side.

Nana holds it together, at least for now,

and calls the hotel where Dad is staying in Greensboro, N.C., for a business

trip.

“Billy, Charlotte has kidnapped the kids,”

Nana said. “They’re headed to Tampa. I just got a call from Alice Burns.”

What’s a dad do with that kind of phone call?

Fall to pieces? Not yet. Follow his instincts? Yep. And for a father, that

almost always means rolling into action – immediately.

Heartbroken, scared and erratic, Dad drives to

Charlotte, N.C., and catches a flight to Tampa. He asks Nana and Pop to leave

their Atlanta home and make the nine-hour drive to Tampa.

No

one knows exactly what their assignment will be once they get to Tampa. They’ll

worry about that once they are all en route.

All of this is happening on a Thursday, I

think, though I can’t swear to it.

Our jail cell in Tampa is a bedroom with

two twin beds. The first night we are there, Cindy and I are awake at midnight,

watching the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson on the small black-and-white TV.

Six-year-olds don’t really get into The Tonight Show, but it’s what’s on, and

it’s providing some background noise and some needed distraction. I’m sleepy

but afraid to go to sleep.

“Isn’t it cool that we get to stay up so

far past our bedtime?” Cindy asked. “We’re watching Johnny Carson. We never get

to watch Johnny Carson. We’re going to be OK, you know. I promise.”

Cindy doesn’t believe that, mind you. But

what she believes isn’t important at the moment. Someone has to take care of

me. So it is going to be an eight-year-old – but at least it is an

eight-year-old who is going to be nine in 11 days. And at least she loves me,

and sometimes even likes me.

“Go to sleep,” she said. “I’ll talk to you

until you fall asleep. And I’ll be here when you wake up. And we’ll go back

home soon, maybe Sunday.”

The next thing I remember, it’s Sunday

morning. Friday and Saturday may have been unremarkable, but I don’t recall.

But on this Sunday morning, Cindy wakes up not feeling well, probably an

emotional wreck from the events of the past few days.

“Stay home with Mary Ellen,” Charlotte

told Cindy. “Get dressed, Bill. We’re going to church.”

In what bizarre world does the kidnapper

take the kid to church? But then again, nothing about this scheme was playing

out in an expected way.

Mary Ellen smokes all day and drinks a

good bit. She is scary looking, and with her gravely and gruff voice, is scary

sounding. She looks disheveled and old, much older than 31, which is what she

is. This is going to be Cindy’s babysitter. But for now, that is Cindy’s cross

to bear. I had been told to get dressed, and that’s exactly what I was going to

do. I figure a woman capable of whatever it is she is doing isn’t one to be

disobeyed.

So with Cindy still in bed, I get dressed,

which means the same clothes I’d been wearing for three days.

It had been raining that morning as we

walked into Hyde Park United Methodist Church. I don’t remember a thing about

the service or what the church looked like on the inside.

I don’t remember praying at church that

morning. I can’t imagine I’d have needed to though. If God wasn’t already at

work on behalf of one of His children, then I’m not sure what I could have said

to convince Him. Again, I didn’t have

those skills anyway. I was at the mercy of others, dependent on grace, even

though I didn’t yet know what the word meant.

I hadn’t for a second questioned that I’d

been wrongfully taken from my home. God didn’t need me to tell Him my story,

lay out the desperation of my situation. He knew.

I

vividly remember the parking lot, though, and walking through it after church.

The dark clouds that had escorted us that morning have broken and the sun is

out.

I get into the front passenger seat, and

because it is humid, I roll down the window the instant the door shuts.

I never saw him coming.

Between the moment in which I got into the

car and when Charlotte is able to pull out, a pair of arms reaches through the

open window, grabs me, and yanks me out of the car.

People in the parking lot are screaming as

they walk out of church. Women use their umbrellas to beat my savior upside his

head.

“Someone call the police!” a woman was

yelling.

“Stop that man!” screams another, while

grabbing at me.

A large, green Chrysler, which is the most

familiar thing I have seen in the last 72 hours, is parked off to the side, the

engine running, the nose pointed toward the parking lot exit.

I came out one car through a window, and

moments later I am being shoved through the door and onto the floorboard of

another car. Then the man jumps into the driver’s seat and speeds away.

“Stay down,” I am told. “Don’t let anyone see

you. The police will be looking for us.”

Things aren’t always as they seem.

Everyone in that church parking lot was

certain they had just seen a kidnapping. Of course, the real one was 72 hours

earlier.

What they were seeing was a rescue, a

dangerous, selfless act that could have left him arrested, assaulted, or worse.

The odds that such a reckless, seemingly random mission would succeed, even if

performed by a trained private investigator or, heck, for that matter a Special

Forces Op, had to be close to zero.

The fact that it is my 61-year-old

paternal grandfather pulling this off requires God’s careful

orchestration. Success for him and my grandmother, his accomplice waiting

in the Chrysler, looks like this:

– They’d have to hope the intel they

had gotten that Charlotte had taken us to church was accurate.

– Pop would have to find me in the parking

lot, snatch me, get me into his car, hide me beneath blankets on the floorboard

and drive to a friend’s house in Tampa, where we’d all switch cars, and drive

to the Orlando airport.

– He’d have to get through security

clearance in Orlando and get us on a plane.

– Then he’d have to hope police weren’t

awaiting the plane’s arrival in Atlanta and get us through, then out of the

Atlanta airport and to our midtown Atlanta home.

The information was accurate. He

succeeded, and it helped that he’d had the forethought to grab Charlotte’s keys

from the ignition and throw them under the car, preventing her from giving

immediate chase.

He also succeeded in hiding me in one car,

and then another, and getting me through two major city airports and eventually

back to the home I was taken from three days earlier.

Indeed, God was intervening.

But what about Cindy?