*The images in this specific piece are granted copyright

privilege by: Public Domain, CCSAL, GNU Free Documentation Licenses, Fair

Use Under The United States Copyright Law, or given copyright privilege by the

copyright holder which is identified beneath the individual photo.

**Some of the links will have to be copied and then posted in

your search engine in order to pull up properly

*** The CRC Blog

welcomes submissions from published and unpublished poets for BACKSTORY OF THE

POEM series. Contact CRC Blog via email

at caccoop@aol.com or personal Facebook messaging at https://www.facebook.com/car.cooper.7

***This is #116 in a

never-ending series called BACKSTORY OF THE POEM where the Chris Rice

Cooper Blog (CRC) focuses on one specific poem and how the poet wrote that

specific poem. All BACKSTORY OF THE POEM links are at the end of

this piece.

“Divorce”

by Joan Barasovska

Can

you go through the step-by-step process of writing this poem from the moment

the idea was first conceived in your brain until final form?

“Divorce,”

the pivotal poem in my first book of poetry, Birthing Age (Finishing Line Press, 2018) (https://www.finishing

“Divorce,”

the pivotal poem in my first book of poetry, Birthing Age (Finishing Line Press, 2018) (https://www.finishing

linepress.com/), was born of another poem,

“Emancipation,” which it replaced in the accepted manuscript.

ibiblio.

org/pjones/

blog/about-

paul-jones/), had read the manuscript and urged me to remove “Emancipation.” That poem’s epigraph is from Abraham Lincoln: “If slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.” I used an extended metaphor of a female house slave who contemplates murder of the master to explain my plight as a subjugated wife and the courage it took, “the final insurrection,” to leave the marriage. The last line is “I am my Great Emancipator.” I was surprised by Paul’s advice. He said that using a slavery metaphor for my life was unacceptable, as I’m a white, middle-class woman. I thought that, being a man and knowing nothing about a woman’s experience, he couldn’t understand the poem.

blog/about-

paul-jones/), had read the manuscript and urged me to remove “Emancipation.” That poem’s epigraph is from Abraham Lincoln: “If slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.” I used an extended metaphor of a female house slave who contemplates murder of the master to explain my plight as a subjugated wife and the courage it took, “the final insurrection,” to leave the marriage. The last line is “I am my Great Emancipator.” I was surprised by Paul’s advice. He said that using a slavery metaphor for my life was unacceptable, as I’m a white, middle-class woman. I thought that, being a man and knowing nothing about a woman’s experience, he couldn’t understand the poem.

But doubts lingered,

so I showed it to another poet friend, Crystal Simone Smith (http://crystal

simone

smith.com/), an African American woman. Crystal is also a poetry editor and her warning was sufficient. I had to pull “Emancipation” and replace it with a poem just as significant and pivotal to the book. She said that though the poem would resonate with those in “this thankless role,” she agreed with Paul. “There is a term used in the black community: ignorant white bliss. I know your heart is in that poem and your intent is honorable, but I would rather you not risk being labeled that way.” She was right. I had not been enslaved, and this was not my metaphor. I needed a metaphor just as compelling but one that arose from my own ancestry. I left for the Gathering of Poets in Winston-Salem, a conference I’ve attended for five years. I took my favorite route, 54 West to the interstate, rural, gentle, and green in early spring.

simone

smith.com/), an African American woman. Crystal is also a poetry editor and her warning was sufficient. I had to pull “Emancipation” and replace it with a poem just as significant and pivotal to the book. She said that though the poem would resonate with those in “this thankless role,” she agreed with Paul. “There is a term used in the black community: ignorant white bliss. I know your heart is in that poem and your intent is honorable, but I would rather you not risk being labeled that way.” She was right. I had not been enslaved, and this was not my metaphor. I needed a metaphor just as compelling but one that arose from my own ancestry. I left for the Gathering of Poets in Winston-Salem, a conference I’ve attended for five years. I took my favorite route, 54 West to the interstate, rural, gentle, and green in early spring.

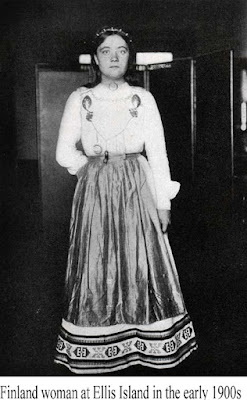

I was struggling for that metaphor and it arrived while I drove and

became the first words of a new poem: “In the shtetl of my heart…” The shtetls

in the Pale of Settlement in late 19th and early 20th

century Russia were the homes of my grandparents before they emigrated to

Philadelphia. Here was the image of oppression that opened the poem to me. The

following day, Saturday, I was distracted during the conference workshops and

readings.

Where were you when you started to actually

write the poem? And please describe the

place in great detail. The poem was written in the driver’s seat of my

2005 silver Honda Accord in the empty parking lot of the Dollar General in

Graham, North Carolina, fifteen miles from my home.

What month and year did you start writing

this poem? It was late March, 2018, on a sunny Sunday morning.

How many drafts of this poem did you write

before going to the final? (And can you share a photograph of your rough drafts

with pen markings on it?) There were many drafts, but fewer than I

usually write because of the time I’d spent writing it in my head while driving

and during stolen moments at the conference. My big problem was the final line,

as I explain below. Unaccountably, I can’t find the notebook where I wrote this

poem—I always compose on paper—or the notes from the 2018 Gathering of

Poets. I have poetry notebooks going

back to the ‘60’s, but not this one.

Were there any lines in any of your rough

drafts of this poem that were not in the final version? And can you share them with us? The only line that changed was the

final one. Originally it was “I am my own Lady Liberty,”

echoing “I am my Great Emancipator” in “Emancipation.” I didn’t like the

boasting tone. In the following week I fretted over it—see photo below—until I

remembered the final words of Emma Lazarus’s (Left) poem engraved at the foot of the

Statue of Liberty, “I lift my lamp beside the golden door.” My grandparents had

walked through that golden door. The final line of “Divorce” became, “A

lifted lamp waited by the foreign shore.”

What do you want readers of this poem to

take from this poem? I want

readers of this poem to briefly experience, in a visceral way, the despair of

this subjugated woman and the exhilaration of her escape.

Which part of the poem was the most

emotional of you to write and why? The line “…across waters I had

never seen” still brings tears to my eyes.

Leaving a very long marriage at 60, leaving its protection and security for the

complete unknown, without plans, was not unlike my grandmother’s leaving her

town of Novgorud, Lithuania, for Philadelphia in 1908.

Anything

you would like to add? “Divorce” was quoted or referred to in all

three of the blurbs of my book. Becky Gould Gibson wrote, “…her extraordinarily

apt and memorable images like ‘the shtetl of my heart’ and ‘the village of my

marriage.’” During readings from my book I recite the poem. It is the poem in Birthing Age that most moves me. It was

the poem I didn’t want to write.

Divorce

In

the shtetl of my heart I hoed weeds in rows

of

cabbages and potatoes. Mud crusted the hem

of

my black wool skirt. I stoked an iron stove

to

boil the thin peasant soup that fed my family.

Daily,

I tied a faded babushka under my chin.

I

muttered curses on the Tsar’s head and wished

him

dead. In the village of my marriage,

I

hid kopeks in a twisted rag, tokens of my rage.

At

last, by moonlight, I trudged miles,

footsore

in worn boots, to book passage

in

steerage across waters I had never seen.

A

lifted lamp waited by the foreign shore.

Joan Barasovska lives in Orange County, North Carolina. She is

an academic therapist in private

practice, working with children with learning disabilities and emotional and

behavioral challenges. Joan cohosts the Flyleaf Books Poetry Series in Chapel

Hill. She serves on the Board of the North Carolina Poetry Society. Birthing

Age, from Finishing Line

Press (2018), is her first book of poetry.

BACKSTORY OF THE POEM

LINKS

001 December 29, 2017

Margo

Berdeshevksy’s “12-24”

002 January 08, 2018

Alexis

Rhone Fancher’s “82 Miles From the Beach, We Order The Lobster At Clear Lake

Café”

003 January 12, 2018

Barbara

Crooker’s “Orange”

004 January 22, 2018

Sonia

Saikaley’s “Modern Matsushima”

005 January 29, 2018

Ellen

Foos’s “Side Yard”

006 February 03, 2018

Susan

Sundwall’s “The Ringmaster”

007 February 09, 2018

Leslea

Newman’s “That Night”

008 February 17, 2018

Alexis

Rhone Fancher “June Fairchild Isn’t Dead”

009 February 24, 2018

Charles

Clifford Brooks III “The Gift of the Year With Granny”

010 March 03, 2018

Scott

Thomas Outlar’s “The Natural Reflection of Your Palms”

011 March 10, 2018

Anya

Francesca Jenkins’s “After Diane Beatty’s Photograph “History Abandoned”

012 March 17, 2018

Angela

Narciso Torres’s “What I Learned This Week”

013 March 24, 2018

Jan

Steckel’s “Holiday On ICE”

014 March 31, 2018

Ibrahim

Honjo’s “Colors”

015 April 14, 2018

Marilyn

Kallett’s “Ode to Disappointment”

016 April 27, 2018

Beth

Copeland’s “Reliquary”

017 May 12, 2018

Marlon

L Fick’s “The Swallows of Barcelona”

018 May 25, 2018

Juliet

Cook’s “ARTERIAL DISCOMBOBULATION”

019 June 09, 2018

Alexis

Rhone Fancher’s “Stiletto Killer. . . A Surmise”

020 June 16, 2018

Charles

Rammelkamp’s “At Last I Can Start Suffering”

021 July 05, 2018

Marla

Shaw O’Neill’s “Wind Chimes”

022 July 13, 2018

Julia Gordon-Bramer’s

“Studying Ariel”

023 July 20, 2018

Bill Yarrow’s “Jesus

Zombie”

024 July 27, 2018

Telaina Eriksen’s “Brag

2016”

025 August 01, 2018

Seth Berg’s “It is only

Yourself that Bends – so Wake up!”

026 August 07, 2018

David Herrle’s “Devil In

the Details”

027 August 13, 2018

Gloria Mindock’s “Carmen

Polo, Lady Necklaces, 2017”

028 August 21, 2018

Connie Post’s “Two

Deaths”

029 August 30, 2018

Mary Harwell Sayler’s

“Faces in a Crowd”

030 September 16, 2018

Larry Jaffe’s “The

Risking Point”

031 September 24,

2018

Mark Lee Webb’s “After

We Drove”

032 October 04, 2018

Melissa Studdard’s

“Astral”

033 October 13, 2018

Robert Craven’s “I Have

A Bass Guitar Called Vanessa”

034 October 17, 2018

David Sullivan’s “Paper Mache

Peaches of Heaven”

035 October 23, 2018

Timothy Gager’s

“Sobriety”

036 October 30, 2018

Gary Glauber’s “The

Second Breakfast”

037 November 04, 2018

Heather Forbes-McKeon’s

“Melania’s Deaf Tone Jacket”

038 November 11, 2018

Andrena Zawinski’s

“Women of the Fields”

039 November 00, 2018

Gordon Hilger’s “Poe”

040 November 16, 2018

Rita Quillen’s “My

Children Question Me About Poetry” and “Deathbed Dreams”

041 November 20, 2018

Jonathan Kevin Rice’s

“Dog Sitting”

042 November 22, 2018

Haroldo Barbosa Filho’s

“Mountain”

043 November 27, 2018

Megan Merchant’s “Grief Flowers”

044 November 30, 2018

Jonathan P Taylor’s

“This poem is too neat”

045 December 03, 2018

Ian Haight’s “Sungmyo

for our Dead Father-in-Law”

046 December 06, 2018

Nancy Dafoe’s “Poem in

the Throat”

047 December 11, 2018

Jeffrey Pearson’s “Memorial

Day”

048 December 14, 2018

Frank Paino’s “Laika”

049 December 15, 2018

Jennifer Martelli’s

“Anniversary”

O50 December 19, 2018

Joseph Ross’s “For Gilberto Ramos, 15, Who Died in

the Texas Desert, June 2014”

051 December 23, 2018

“The Persistence of

Music”

by Anatoly Molotkov

052 December 27, 2018

“Under Surveillance”

by Michael Farry

053 December 28, 2018

“Grand Finale”

by Renuka Raghavan

054 December 29, 2018

“Aftermath”

by Gene Barry

055 January 2, 2019

“&”

by Larissa Shmailo

056 January 7, 2019

“The Seamstress:

by Len Kuntz

057 January 10, 2019

"Natural History"

by Camille T Dungy

058 January 11, 2019

“BLOCKADE”

by Brian Burmeister

059 January 12, 2019

“Lost”

by Clint Margrave

060 January 14, 2019

“Menopause”

by Pat Durmon

061 January 19, 2019

“Neptune’s Choir”

by Linda Imbler

062 January 22, 2019

“Views From the

Driveway”

by Amy Barone

063 January 25, 2019

“The heron leaves her

haunts in the marsh”

by Gail Wronsky

064 January 30, 2019

“Shiprock”

by Terry Lucas

065 February 02, 2019

“Summer 1970, The

University of Virginia Opens to Women in the Fall”

by Alarie Tennille

066 February 05, 2019

“At School They Learn

Nouns”

by Patrick Bizzaro

067 February 06, 2019

“I Must Not Breathe”

by Angela Jackson-Brown

068 February 11, 2019

“Lunch on City Island,

Early June”

by Christine Potter

069 February 12, 2019

“Singing”

by Andrew McFadyen-Ketchum

070 February 14, 2019

“Daily Commute”

by Christopher P. Locke

071 February 18, 2019

“How Silent The Trees”

by Wyn Cooper

072 February 20, 2019

“A New Psalm

of Montreal”

by Sheenagh Pugh

073 February 23, 2019

“Make Me A

Butterfly”

by Amy Barbera

074 February 26, 2019

“Anthem”

by Sandy Coomer

075 March 4, 2019

“Shape of a Violin”

by Kelly Powell

076 March 5, 2019

“Inward Oracle”

by J.P. Dancing Bear

077 March 7, 2019

“I Broke

My Bust Of Jesus”

by Susan Sundwall

078 March 9, 2019

“My Mother

at 19”

by John Guzlowski

079 March 10, 2019

“Paddling”

by Chera Hammons Miller

080 March 12, 2019

“Of Water

and Echo”

by Gillian Cummings

081 082

083 March 14, 2019

“Little

Political Sense” “Crossing Kansas with

Jim

Morrison” “The Land of Sky and Blue Waters”

by Dr. Lindsey

Martin-Bowen

084 March 15, 2019

“A Tune To

Remember”

by Anna Evans

085 March 19, 2019

“At the

End of Time (Wish You Were Here)

by Jeannine Hall Gailey

086 March 20, 2019

“Garden of

Gethsemane”

by Marletta Hemphill

087 March 21, 2019

“Letters

From a War”

by Chelsea Dingman

088 March 26, 2019

“HAT”

by Bob Heman

089 March 27, 2019

“Clay for

the Potter”

by Belinda Bourgeois

#090 March 30, 2019

“The Pose”

by John Hicks

#091 April 2, 2019

“Last

Night at the Wursthaus”

by Doug Holder

#092 April 4, 2019

“Original

Sin”

by Diane Lockward

#093 April 5, 2019

“A Father

Calls to his child on liveleak”

by Stephen Byrne

#094 April 8, 2019

“XX”

by Marc Zegans

#095 April 12, 2019

“Landscape

and Still Life”

by Marjorie Maddox

#096 April 16, 2019

“Strawberries

Have Been Growing Here for Hundreds of

Years”

by Mary Ellen Lough

#097 April 17, 2019

“The New

Science of Slippery Surfaces”

by Donna Spruijt-Metz

#098 April 19, 2019

“Tennessee

Epithalamium”

by Alyse Knorr

#099 April 20, 2019

“Mermaid,

1969”

by Tameca L. Coleman

#100 April 21, 2019

“How Do

You Know?”

by Stephanie

#101 April 23, 2019

“Rare Book

and Reader”

by Ned Balbo

#102 April 26, 2019

“THUNDER”

by Jefferson Carter

#103 May 01, 2019

“The sight

of a million angels”

by Jenneth Graser

#104 May 09, 2019

“How to

tell my dog I’m dying”

by Richard Fox

#105 May 17, 2019

“Promises

Had Been Made”

by Sarah Sarai

#106 June 01, 2019

“i sold

your car today”

by Pamela Twining

#107 June 02, 2019

“Abandoned

Stable”

by Nancy Susanna Breen

#108 June 05, 2019

“Cupcake”

by Julene Tripp Weaver

#109 June 6, 2019

“Bobby’s

Story”

by Jimmy Pappas

#110 June 10, 2019

“When You

Ask Me to Tell You About My Father”

by Pauletta Hansel

#111 Backstory of the

Poem’s

“Cemetery

Mailbox”

by Jennifer Horne

#112 Backstory of the Poem’s

“Relics”

by Kate Peper

#113 Backstory of the

Poem’s

“Q”

by Jennifer Johnson

#114 Backstory of the

Poem’s

“Brushing My Hair”

by Tammika Dorsey Jones

#115 Backstory of the

Poem

“Because the Birds Will

Survive, Too”

by Katherine Riegel

#116 Backstory of the

Poem

“DIVORCE”

by Joan Barasovska

“DIVORCE”

by Joan Barasovska