*The images in this specific piece are granted copyright privilege by: Public Domain, CCSAL, GNU Free Documentation Licenses, Fair Use Under The United States Copyright Law, or given copyright privilege by the copyright holder which is identified beneath the individual photo.

**Some of the links will have to be copied and then posted in your search engine in order to pull up properly

*** The CRC Blog welcomes submissions from published and unpublished poets for BACKSTORY OF THE POEM series. Contact CRC Blog via email at caccoop@aol.com or personal Facebook messaging at https://www.facebook.com/car.cooper.7

***This is #158 in a never-ending series called BACKSTORY OF THE POEM where the Chris Rice Cooper Blog (CRC) focuses on one specific poem and how the poet wrote that specific poem. All BACKSTORY OF THE POEM links are at the end of this piece.

“Why Otters Hold Hands”

by William Walsh

by William Walsh

Can you go through the step-by-step process of writing this poem from the moment the idea was first conceived in your brain until final form? I never teach my own poems in workshop or ask my students to read my work; however, one day in the fall 2018, in workshop, a student asked if I would take them through the step-by-step process of writing a poem, of how I wrote a poem. At the time, I did not have any new poems or drafts, and with a new manuscript in hand, I was sort of on a break from poetry for a month or so as I worked on other projects.

I wrote a horrible first draft of a poem about my daughter (Right) at her cross-country meet on a Saturday, where, because I was standing too close to the school tent, she shooed me away, as if embarrassed to be seen with me. That was a first “shooing away” in my life by her. My boys never shooed me away, but Olivia shooed me away twice that morning. That was the impetus for the poem.

I read the poem to the class and then allowed the students to edit the poem. They dove right in to tell me what was not working and what they liked or thought might be salvageable. Each week they spent about five to ten minutes workshopping the poem, which allowed them to have some ownership in the editorial process by providing suggestions, comments, edits, and so forth. It also provided a look into how “I did it.” They had the opportunity to see the poem develop, which is an important element in the creative process. For the longest time, to me, it was simply an exercise, a poem I was going to completely dismiss and throw away after the semester ended. The idea was to demonstrate to the students that not every poem is written in one or two drafts, that time must be invested for thinking about the poems, the ideas, the possibilities, editing it, and returning days and weeks later with a clearer perspective.

It took about two months of editing until the poem was reasonably in shape. I worked a lot on the poem, sometimes a few hours per day because I did not want to disappoint the students. I wanted them to see first-hand what often goes into writing one poem. One of the last things to present itself was the form. Up until the end, it was free verse, staggered lines and stanzas. The couplets developed around the last two drafts, and as soon as I had the couplets, I knew that was the form I wanted. It felt perfect. When it was “finished” for the class, one of the students gave it to another professor, who, upon reading it began to cry. This student then gave it to his father to read that same weekend, and he, too, cried. I began to notice that I had struck a chord with men. I tweaked the poem and ended up loving it enough to add it to the new collection. It was the last poem I included.

I was able to guide my students through my process of writing a poem, which is different for each poet; however, it at least gave them insight into what is oftentimes required. In my class we always identify the Subject, Conflict, and Metaphor in a poem in order to understand it as fully as possible. It helps to immediately break through all the other problems if we can identify those. “Otters” and the process of writing “Otters” demonstrated how to take a bad draft and work towards the subject, conflict, and metaphor. They ended up learning how one poet works. I’ve since heard from those students that it was helpful.

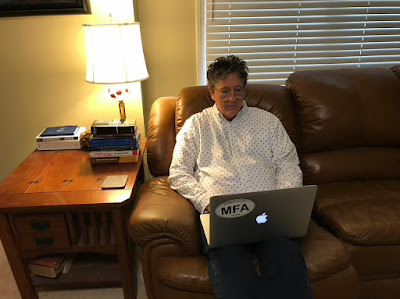

Where were you when you started to actually write the poem? And please describe the place in great detail. I was at my house in Sandy Springs, GA, sitting downstairs in the basement, which is my office and is finished off. It is quiet and relaxing. I was sitting on the sofa with a blank piece of paper and a blue pen where I began scribbling my notes. That was on the Monday, just two days after my daughter shooed me away. I wanted to capture that emotion of being cast off.

My sitting area is comfortable. It is a light brown leather sofa. There is a mission-style end table with antique lamps that belonged to my grandmother. She bought it in the 1940s. My cousin mailed them to me years ago and the lampshades were crushed in transit, so I have new, white shades on them. I also had the wiring replaced. In front of me are my bookshelves with the books in alphabetical order according to the author’s last name. There are about 1000 books. I had more but years ago, I donated about half to Goodwill. Books are everywhere on the floor, in stacks. On the coffee table there is a photo book on Yeats’ Ireland, as well as a large wooden bowl from the 1700s my mother bought back in the 1970s in Pennsylvania. On top of the shelves is a golf trophy from when I played on an amateur tour and won several tournaments. There is a ceramic alligator bank my mother made for me when I was seven, some childhood artwork, and original paintings on the walls. I have a beautiful flat screen TV that is not hooked up so I cannot watch TV while I am downstairs. I recline the sofa, play instrumental music to relax and write. I’m a rock’n’roll fan of Led Zeppelin, KISS, Queen, and just about any pop/rock music. However, I very much enjoy popular music set to instrumental scores. I enjoy filtering out each instrument and listening while I write. Usually, my dog, Luke, sleeps at the other end of the sofa while I write. He’s half Mastiff and half Boxer. He weighs about 85 pounds. I sometimes read a poem to him so that I can hear it aloud. He has yet to provide any substantive feedback, but there is always the possibility something I write might move his spirit.

What month and year did you start writing this poem? October 2018

How many drafts of this poem did you write before going to the final? (And can you share a photograph of your rough drafts with pen markings on it?) I do not have any draft of the poem. I am a minimalist and do not keep anything. I shred everything to be recycled. However, from beginning to end, I probably had 30 to 40 drafts. I edited it every other day for two months. (Below Right: Olivia Walsh with Luke)

Were there any lines in any of your rough drafts of this poem that were not in the final version? And can you share them with us? Most of the original drafts were, at some point, cut. I tossed everything in the garbage except the final poem. I see no reason to keep things. Some lines morphed into other lines and were moved around and switched back and forth in draft after draft. These are the only lines I have found that I removed from the original draft:

Things happen in war

that need to be forgiven

I do not remember how these two lines pertained to the poem. For some reason, they were cut. I saved them but have not used them yet in another poem. I’m not sure why I saved them, except that I like the idea of forgiveness.

What do you want readers of this poem to take from this poem? “Why Otters Hold Hands” has become the seminal poem in the collection, oddly enough. Go figure. I could never have imagined this would occur. There is a metaphor running through the poem, and what I would like the reader to experience is the father-daughter relationship and how the father is there to support his daughter running the high school race, but, in truth, he knows she is running away from him. She must. She needs to run. She needs to grow, and the only method by which she can fulfill that journey is to run from the father. It hurts the father deeply, but he must stand there and take it like a man, because, there is much more of the same thing in the future. Get used to it buddy! And, yet, the idea of why otters hold hands is so they will not drift away.

The father does not want his daughter to drift permanently away, so he must allow her to run away, with the hope that she will return. And, like in the beginning of the poem, what the father wants are all the things in his life that are simple and quiet and known to him, such as his daughter’s love. He wants everything to be the way it was. Unfortunately, the daughter has different plans for her life. Still, otters hold hands so they will not drift apart.

Which part of the poem was the most emotional of you to write and why? The end where the father realizes his daughter is running, not just the cross-country race, but away from him. He must allow her to have this freedom. It is a difficult situation for any parent.

Has this poem been published before? And if so where? The dean of the university read the poem and asked to publish it in the university literary journal, Sanctuary, which they did. It’s a nice journal, very professionally produced. It is also in my new collection of poems, Fly Fishing in Times Square, which will be released on January 2, 2020. It won the Editor’s Prize at Červená Barva Press, having beat out 400+ manuscripts. I am proud of that.

Has this poem been published before? And if so where? The dean of the university read the poem and asked to publish it in the university literary journal, Sanctuary, which they did. It’s a nice journal, very professionally produced. It is also in my new collection of poems, Fly Fishing in Times Square, which will be released on January 2, 2020. It won the Editor’s Prize at Červená Barva Press, having beat out 400+ manuscripts. I am proud of that.

Anything you would like to add? As Winston Churchill said, “Never give up.” I did not think much of the original draft or drafts after that, but I marched on because my students needed this very hands-on example for how a poet writes a poem. I guess they needed to learn by example. Eventually, a miracle occurred, and a poem fell into my lap. If you are serious about poetry, keep writing every day. Edit every day. Think about poetry every day. Read, read, read. Read poetry every day. Why? Because poetry changes people’s lives. In some places, it saves lives. It also helps us understand more about our lives.

Why Otters Hold Hands

I want to live in a small town like Lakewood,

where the fastest thing is a sailboat without wind.

I want to know the world is safe for my daughter,

that I never have to share my failures, a place,

where, if I ever lose my religion again, someone

will return it to my house, ring the bell

and if I am not home, they will leave

it on the mat. I want a kid selling scout popcorn

or Christmas paper to stop me at the grocery store

and I want a kid on every corner selling Kool-Aid

from a card table, and a kid asking to rake my leaves.

I want the woman down the street to wear her bikini

while pushing the mower. I want a parade through town

every Fourth of July, and I want Friday fish fries

at the church. I want to hear my daughter singing

in the shower while I’m cooking spaghetti, straining

the angel hair while she’s crowing like Iris Dement,

lost to herself, having forgotten the rest of the world can hear her.

I want to sit at the kitchen table, listening, just listening.

There’s so much, and yet, I can never have it again:

Dora the Explorer, helicopter rides, or watching a documentary

on The Life of Otters, how we laughed

at the Dog Fails on YouTube, scrunched up together on the sofa

eating popcorn with too much salt, dripping with butter,

and drinking Cokes on a school night.

I want my daughter to walk with me

in the mall and not down the other side

like I am an alien, the family embarrassment

who mortifies her. Because,

this morning, at the cross-country meet

my daughter shooed me away when I stood too close

to the school tent talking to the other parents.

Loosening up, the girls stretch, run wind sprints

toward womanhood. There’s no chance of her winning this race,

just work on your best time, I told her. She shooed me away again.

I know this is the future, what I haven’t quite prepared for.

There will be other, more important, races, I want to say.

The field is stacked with nearly two hundred girls,

most giggling about something the parents don’t understand.

As she pushes forward through the crown of girlhood,

I remember the otters holding hands while sleeping

so they won’t drift apart.

William Walsh is the director of the Reinhardt University B.F.A. and M.F.A. programs and a southern narrative poet in the tradition of James Dickey, David Bottoms, and Fred Chappell. In addition to his new collection of poems, Fly Fishing in Times Square, he is the author of three novels: The Pig Rider, The Boomerang Mattress and Haircuts for the Dead (Finalists and Semi-Finalists in the William Faulkner Pirate Alley Prize). His other books include: Speak So I Shall Know Thee: Interviews with Southern Writers (McFarland, 1990); The Ordinary Life of a Sculptor (Sandstone, 1993); The Conscience of My Other Being (Cherokee Publishers, 2005); Under the Rock Umbrella: Contemporary American Poets from 1951-1977 (Mercer, 2006); David Bottoms: Critical Essays and Interviews (McFarland, 2010), and Lost In the White Ruins (2014).

His work has appeared in AWP Chronicle, Cimarron Review, Five Points, Flannery O’Connor Review, The Georgia Review, James Dickey Review, The Kenyon Review, Literary Matters, Michigan Quarterly Review, North American Review, Poetry Daily, Poets & Writers, Rattle, Shenandoah, Slant, and Valparaiso Poetry Review.

His literary interviews have been published in over fifty journals, and include, among others, Czeslaw Milosz, Joseph Brodsky, A.R. Ammons, Doris Betts, Richard Blanco, Eavan Boland, Pat Conroy, David, Bottoms, Harry Crews, James Dickey, Ariel Dorfman, Mark Doty, Rita Dove, Stephen Dunn, Eamon Grennan, Mary Hood, Edward Jones, Madison Jones, Donald Justice, George Singleton, Ursula Le Guin, Andrew Lytle, and Lee Smith.

BACKSTORY OF THE POEM LINKS

001 December 29, 2017

Margo Berdeshevksy’s “12-24”

002 January 08, 2018

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s “82 Miles From the Beach, We Order The Lobster At Clear Lake Café”

003 January 12, 2018

Barbara Crooker’s “Orange”

004 January 22, 2018

Sonia Saikaley’s “Modern Matsushima”

005 January 29, 2018

Ellen Foos’s “Side Yard”

006 February 03, 2018

Susan Sundwall’s “The Ringmaster”

007 February 09, 2018

Leslea Newman’s “That Night”

008 February 17, 2018

Alexis Rhone Fancher “June Fairchild Isn’t Dead”

009 February 24, 2018

Charles Clifford Brooks III “The Gift of the Year With Granny”

010 March 03, 2018

Scott Thomas Outlar’s “The Natural Reflection of Your Palms”

011 March 10, 2018

Anya Francesca Jenkins’s “After Diane Beatty’s Photograph “History Abandoned”

012 March 17, 2018

Angela Narciso Torres’s “What I Learned This Week”

013 March 24, 2018

Jan Steckel’s “Holiday On ICE”

014 March 31, 2018

Ibrahim Honjo’s “Colors”

015 April 14, 2018

Marilyn Kallett’s “Ode to Disappointment”

016 April 27, 2018

Beth Copeland’s “Reliquary”

017 May 12, 2018

Marlon L Fick’s “The Swallows of Barcelona”

018 May 25, 2018

Juliet Cook’s “ARTERIAL DISCOMBOBULATION”

019 June 09, 2018

Alexis Rhone Fancher’s “Stiletto Killer. . . A Surmise”

020 June 16, 2018

Charles Rammelkamp’s “At Last I Can Start Suffering”

021 July 05, 2018

Marla Shaw O’Neill’s “Wind Chimes”

022 July 13, 2018

Julia Gordon-Bramer’s “Studying Ariel”

023 July 20, 2018

Bill Yarrow’s “Jesus Zombie”

024 July 27, 2018

Telaina Eriksen’s “Brag 2016”

025 August 01, 2018

Seth Berg’s “It is only Yourself that Bends – so Wake up!”

026 August 07, 2018

David Herrle’s “Devil In the Details”

027 August 13, 2018

Gloria Mindock’s “Carmen Polo, Lady Necklaces, 2017”

028 August 21, 2018

Connie Post’s “Two Deaths”

029 August 30, 2018

Mary Harwell Sayler’s “Faces in a Crowd”

030 September 16, 2018

Larry Jaffe’s “The Risking Point”

031 September 24, 2018

Mark Lee Webb’s “After We Drove”

032 October 04, 2018

Melissa Studdard’s “Astral”

033 October 13, 2018

Robert Craven’s “I Have A Bass Guitar Called Vanessa”

034 October 17, 2018

David Sullivan’s “Paper Mache Peaches of Heaven”

035 October 23, 2018

Timothy Gager’s “Sobriety”

036 October 30, 2018

Gary Glauber’s “The Second Breakfast”

037 November 04, 2018

Heather Forbes-McKeon’s “Melania’s Deaf Tone Jacket”

038 November 11, 2018

Andrena Zawinski’s “Women of the Fields”

039 November 00, 2018

Gordon Hilger’s “Poe”

040 November 16, 2018

Rita Quillen’s “My Children Question Me About Poetry” and “Deathbed Dreams”

041 November 20, 2018

Jonathan Kevin Rice’s “Dog Sitting”

042 November 22, 2018

Haroldo Barbosa Filho’s “Mountain”

043 November 27, 2018

Megan Merchant’s “Grief Flowers”

044 November 30, 2018

Jonathan P Taylor’s “This poem is too neat”

045 December 03, 2018

Ian Haight’s “Sungmyo for our Dead Father-in-Law”

046 December 06, 2018

Nancy Dafoe’s “Poem in the Throat”

047 December 11, 2018

Jeffrey Pearson’s “Memorial Day”

048 December 14, 2018

Frank Paino’s “Laika”

049 December 15, 2018

Jennifer Martelli’s “Anniversary”

O50 December 19, 2018

Joseph Ross’s “For Gilberto Ramos, 15, Who Died in the Texas Desert, June 2014”

051 December 23, 2018

“The Persistence of Music”

by Anatoly Molotkov

052 December 27, 2018

“Under Surveillance”

by Michael Farry

053 December 28, 2018

“Grand Finale”

by Renuka Raghavan

054 December 29, 2018

“Aftermath”

by Gene Barry

055 January 2, 2019

“&”

by Larissa Shmailo

056 January 7, 2019

“The Seamstress:

by Len Kuntz

057 January 10, 2019

"Natural History"

by Camille T Dungy

058 January 11, 2019

“BLOCKADE”

by Brian Burmeister

059 January 12, 2019

“Lost”

by Clint Margrave

060 January 14, 2019

“Menopause”

by Pat Durmon

061 January 19, 2019

“Neptune’s Choir”

by Linda Imbler

062 January 22, 2019

“Views From the Driveway”

by Amy Barone

063 January 25, 2019

“The heron leaves her haunts in the marsh”

by Gail Wronsky

064 January 30, 2019

“Shiprock”

by Terry Lucas

065 February 02, 2019

“Summer 1970, The University of Virginia Opens to Women in the Fall”

by Alarie Tennille

066 February 05, 2019

“At School They Learn Nouns”

by Patrick Bizzaro

067 February 06, 2019

“I Must Not Breathe”

by Angela Jackson-Brown

068 February 11, 2019

“Lunch on City Island, Early June”

by Christine Potter

069 February 12, 2019

“Singing”

by Andrew McFadyen-Ketchum

070 February 14, 2019

“Daily Commute”

by Christopher P. Locke

071 February 18, 2019

“How Silent The Trees”

by Wyn Cooper

072 February 20, 2019

“A New Psalm of Montreal”

by Sheenagh Pugh

073 February 23, 2019

“Make Me A Butterfly”

by Amy Barbera

074 February 26, 2019

“Anthem”

by Sandy Coomer

075 March 4, 2019

“Shape of a Violin”

by Kelly Powell

076 March 5, 2019

“Inward Oracle”

by J.P. Dancing Bear

077 March 7, 2019

“I Broke My Bust Of Jesus”

by Susan Sundwall

078 March 9, 2019

“My Mother at 19”

by John Guzlowski

079 March 10, 2019

“Paddling”

by Chera Hammons Miller

080 March 12, 2019

“Of Water and Echo”

by Gillian Cummings

081 082 083 March 14, 2019

“Little Political Sense” “Crossing Kansas with Jim

Morrison” “The Land of Sky and Blue Waters”

by Dr. Lindsey Martin-Bowen

084 March 15, 2019

“A Tune To Remember”

by Anna Evans

085 March 19, 2019

“At the End of Time (Wish You Were Here)

by Jeannine Hall Gailey

086 March 20, 2019

“Garden of Gethsemane”

by Marletta Hemphill

087 March 21, 2019

“Letters From a War”

by Chelsea Dingman

088 March 26, 2019

“HAT”

by Bob Heman

089 March 27, 2019

“Clay for the Potter”

by Belinda Bourgeois

#090 March 30, 2019

“The Pose”

by John Hicks

#091 April 2, 2019

“Last Night at the Wursthaus”

by Doug Holder

#092 April 4, 2019

“Original Sin”

by Diane Lockward

#093 April 5, 2019

“A Father Calls to his child on liveleak”

by Stephen Byrne

#094 April 8, 2019

“XX”

by Marc Zegans

#095 April 12, 2019

“Landscape and Still Life”

by Marjorie Maddox

#096 April 16, 2019

“Strawberries Have Been Growing Here for Hundreds of

Years”

by Mary Ellen Lough

#097 April 17, 2019

“The New Science of Slippery Surfaces”

by Donna Spruijt-Metz

#098 April 19, 2019

“Tennessee Epithalamium”

by Alyse Knorr

#099 April 20, 2019

“Mermaid, 1969”

by Tameca L. Coleman

#100 April 21, 2019

“How Do You Know?”

by Stephanie

#101 April 23, 2019

“Rare Book and Reader”

by Ned Balbo

#102 April 26, 2019

“THUNDER”

by Jefferson Carter

#103 May 01, 2019

“The sight of a million angels”

by Jenneth Graser

#104 May 09, 2019

“How to tell my dog I’m dying”

by Richard Fox

#105 May 17, 2019

“Promises Had Been Made”

by Sarah Sarai

#106 June 01, 2019

“i sold your car today”

by Pamela Twining

#107 June 02, 2019

“Abandoned Stable”

by Nancy Susanna Breen

#108 June 05, 2019

“Cupcake”

by Julene Tripp Weaver

#109 June 6, 2019

“Bobby’s Story”

by Jimmy Pappas

#110 June 10, 2019

“When You Ask Me to Tell You About My Father”

by Pauletta Hansel

#111 Backstory of the Poem’s

“Cemetery Mailbox”

by Jennifer Horne

#112 Backstory of the Poem’s

“Relics”

by Kate Peper

#113 Backstory of the Poem’s

“Q”

by Jennifer Johnson

#114 Backstory of the Poem’s

“Brushing My Hair”

by Tammika Dorsey Jones

#115 Backstory of the Poem

“Because the Birds Will Survive, Too”

by Katherine Riegel

#116 Backstory of the Poem

“DIVORCE”

“DIVORCE”

by Joan Barasovska

#117 Backstory of the Poem

“NEW YEAR”S EVE 2016”

by Michael Meyerhofer

#118 Backstory of the Poem

“Dear the estranged,”

by Gina Tron

#119 Backstory of the Poem

“In Remembrance of Them”

by Janet Renee Cryer

#120 Backstory of the Poem

“Horse Fly Grade Card, Doesn’t Play Well With Others”

by David L. Harrison

#121 Backstory of the Poem

“My Mother’s Cookbook”

by Rachael Ikins

#122 Backstory of the Poem

“Cousins I Never Met”

by Maureen Kadish Sherbondy

#123 Backstory of the Poem

“To Those Who Were Our First Gods”

by Nickole Brown

#124 Backstory of the Poem

“Looking For Sunsets (In the Early Morning)”

“Looking For Sunsets (In the Early Morning)”

by Paul Levinson

#125 Backstory of the Poem

“Tracy”

by Tiff Holland

#126 Backstory of the Poem

“Legs”

by Cindy Hochman

“Legs”

by Cindy Hochman

#127 Backstory of the Poem

“Anathema”

“Anathema”

by Natasha Saje

#128 Backstory of the Poem

“How to Explain Fertility When an Acquaintance Asks Casually”

by Allison Blevins

#129 Backstory of the Poem

“The Art of Meditation In Tennessee”

by Linda Parsons

#130 Backstory of the Poem

“Schooling High, In Beslan”

by Satabdi Saha

#131 Backstory of the Poem

““Baby Jacob survives the Oso Landslide, 2014”

by Amie Zimmerman

#132 Backstory of the Poem

“Our Age of Anxiety”

by Henry Israeli

#133 Backstory of the Poem

“Earth Cries; Heaven Smiles”

by Ken Allan Dronsfield

#134 Backstory of the Poem

“Eons”

by Janine Canan

#135 Backstory of the Poem

“Sworn”

by Catherine Zickgraf

#136 Backstory of the Poem

“Bushwick Blue”

by Susana H. Case

#137 Backstory of the Poem

“Then She Was Forever”

by Paula Persoleo

#138 Backstory of the Poem

“Enough”

by Kris Bigalk

#139 Backstory of the Poem

“From Ghosts of the Upper Floor”

by Tony Trigilio

#140 Backstory of the Poem

“Cloud Audience”

by Wanita Zumbrunnen

#141 Backstory of the Poem

“Condition Center”

by Matthew Freeman

#142 Backstory of the Poem

“Adventuresome Woman”

by Cheryl Suchors

#143 Backstory of the Poem

“The Way Back”

“The Way Back”

by Robert Walicki

#144 Backstory of the Poem

“If I Had Three Lives”

by Sarah Russell

#145 Backstory of the Poem

“Reservoir”

by Andrea Rexilius

#146 Backstory of the Poem

“The Night Before Our Dog Died”

by Melissa Fite Johnson

#147 Backstory of the Poem

“Pileated”

by David Anthony Sam

#148 Backstory of the Poem

“A Kitchen Argument”

by Matthew Gwathmey

https://chrisricecooper.blogspot.com/2020/01/148-backstory-of-poem-kitchen-argument.html

https://chrisricecooper.blogspot.com/2020/01/148-backstory-of-poem-kitchen-argument.html

#149 Backstory of the Poem

“Insulation”

by Bruce Kauffman

#150 Backstory of the Poem

“I Will Tell You Where I’ve Been”

by Justin Hamm

#151 Backstory of the Poem

“Comfort”

by Michael A Griffith

#152 Backstory of the Poem

“VAN GOGH TO HIS MISTRESS”

by Margo Taft Stever

“VAN GOGH TO HIS MISTRESS”

by Margo Taft Stever

#153 Backstory of the Poem

“1. Girl”

by Margaret Manuel

#154 Backstory of the Poem

“Trading Places”

by Maria Chisolm

#155 Backstory of the Poem

“The Reoccurring Woman”

by Debra May

#156 Backstory of the Poem

“Word Falling”

by Sheryl St. Germain

#157 Backstory of the Poem

“Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup of 7,000 Jews Detained in an

Arena”

by Liz Marlow

#158 Backstory of the Poem

“Why Otters Hold Hands”